When I was a child, my father took me to the river—the mighty Ohio—so I could experience the extraordinary feat of walking on frozen water. It was an unforgettable experience that took place in January 1977, during one of the coldest winters in Cincinnati’s history. The temperature dropped below zero for twenty-eight days straight, resulting in a twelve-inch-thick freeze of the river. This transformed the Ohio River into a magnificent bridge, connecting the regions of Ohio and Kentucky, and symbolizing the unity of the North and the South. While the Ohio River used to freeze more frequently in the 19th century, it has become a rare occurrence in the 20th century. Due to climate change, it is highly unlikely that the river will freeze again in the future. However, the memory of the frozen river and the sense of the impossible turning into reality will always remain with me.

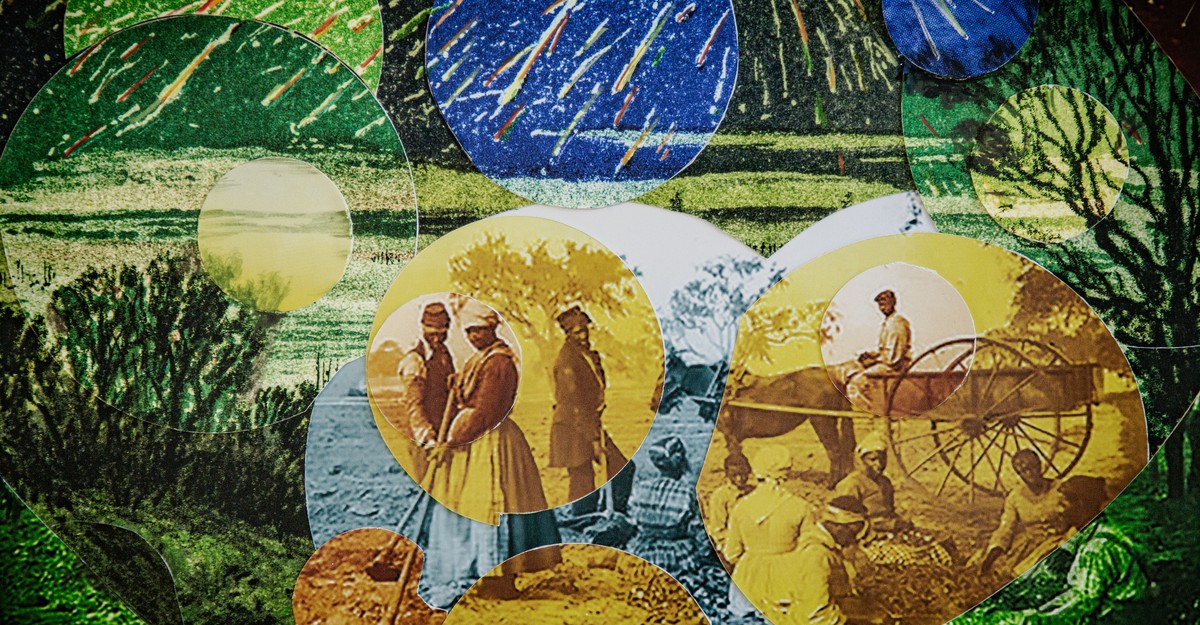

As I reflect on that awe-inspiring sight, I cannot help but acknowledge the historical significance of the Ohio River, particularly for enslaved Black individuals seeking freedom. It was not until later in life that I discovered the river’s role as a pathway to liberation. In 1856, on a bitterly cold January day, Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman in Kentucky, attempted to escape to the North with her family by crossing the frozen river. Margaret was not alone in her quest for freedom that night. Nine other enslaved individuals joined her in what the newspapers derogatorily referred to as a “stampede of slaves” across the “ice bridge” of the Ohio River.

Margaret’s story was well-known in the 19th century but had faded into obscurity until Toni Morrison drew inspiration from it for her novel Beloved. Margaret had been born into slavery near the river in Kentucky. As a teenager, she was subjected to the predatory advances of Archibald Gaines, the man who owned her. By the time she was twenty-two, Margaret had informally married another enslaved man named Robert Garner (as their union was not legally recognized) and had four children. Some of these children may have been fathered by Gaines, with the youngest child reportedly having a fair complexion. When Margaret found herself pregnant with a fifth child, she made the desperate decision to escape up the river, defying the odds and risking everything for the chance at freedom.

The family managed to reach the home of Margaret’s free relatives in Ohio, but their respite was short-lived. Armed officers accompanied Archibald Gaines as he stormed the house, recapturing Margaret and her family. Faced with the prospect of returning to a life of enslavement, Margaret made the heart-wrenching choice to take the life of her youngest child before allowing them to once again be subjected to bondage. She was put on trial and eventually handed back to Gaines, who promptly sold them to the Deep South.

While Margaret’s story ended in tragedy, there were others who successfully escaped to lasting freedom by crossing the frozen Ohio River. Rutherford B. Hayes, the former U.S. President, recounted that during the winters of 1850 to 1856, when the Fugitive Slave Act was in effect, the river froze consistently, providing opportunities for escape. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed for the capture and forced return of escaped slaves and instilled fear within free Black communities. However, many brave individuals seized the chance to liberate themselves despite the dangers posed by this law.

The frozen Ohio River during those five years seemingly defied chance and became a symbol of hope for those seeking freedom. As a black woman writer, I draw inspiration from this resilient river. It serves as a reminder that despite the trauma of history and the challenges we face today, nature can act as a bridge, connecting us to a brighter future.

“The outdoors” encompasses a vast array of experiences and environments. However, it is often portrayed as a space exclusively frequented by white individuals. This narrow perception overlooks the rich history of African Americans in outdoor spaces. Even amidst exploitation and labor, many enslaved individuals found solace and wisdom in nature. They drew inspiration from the untamed wilderness on the fringes of human settlements, where different rules governed life. Nature became their classroom, teaching them to question societal norms and practices.

My perspective on Black liberation activists like Harriet Tubman shifted when I considered the profound ecological awareness required to survive slavery and navigate through the wild terrains they encountered. Tubman, born into slavery around 1821, possessed an innate connection to both land and water. She spent her formative years immersed in the outdoors—like a neglected weed, unaware of liberty. She despised the restrictions of domestic work and feared the confinement of enclosed spaces where she was subject to surveillance and mistreatment. Tubman’s refusal to conform to societal expectations led her to choose a life outdoors, which became her primary workplace as her owners recognized her immense skill in agricultural and forestry labor. Despite the exploitation she endured, Tubman harbored a deep love for the land that transcended the brutality of slavery.

From an early age, Tubman experienced the devastating loss of her siblings to the slave trade, fueling her desire for freedom. At just six or seven years old, she was hired out by Edward Brodess, who also owned Tubman’s mother. Miles away from her family, Tubman toiled under the employ of James Cook and his wife, performing various tasks indoors and venturing into the cold, brackish waters near the Chesapeake Bay to retrieve muskrats from traps laid by Cook. She fell ill with measles but was eventually healed by her mother’s care, only to be leased out once more by Brodess.

Her second assignment placed her in the home of a white woman named Miss Susan, who had an infant. Tubman’s inability to keep the baby quiet and maintain the household to Susan’s satisfaction resulted in regular beatings and scars that would mark her for life. Tubman once took a lump of sugar without permission, prompting Susan to reach for the whip. Tubman fled and sought refuge in a pigpen on a nearby farm, hiding among the pigs and their mother for several days until the fear of being harmed compelled her to return to Susan’s household. Her return was met with merciless beatings.

Despite the severe consequences she faced, Tubman learned that she could survive on her own in the wilderness if she possessed the audacity and resilience to endure deprivation and punishment.

In later years, Tubman worked for a timber business, where she discovered the secrets of the forest. She became adept at identifying edible leaves, berries, and nuts and familiarized herself with the directional flow of water—north to south. In 1849, when she was around twenty-seven years old, she used this knowledge to escape to Philadelphia, following the North Star as her guide. Tubman later returned to the South in December 1854 to rescue her brothers. Over the next decade, she made approximately thirteen trips, helping seventy to eighty enslaved individuals gain their freedom.

Tubman preferred to travel during the winter months, as longer nights provided greater cover for the fugitives. Guided by the North Star, she navigated the treacherous terrains and sustained herself and her companions with foraged food when resources were scarce. Remarkably, Tubman and her fellow travelers, including infants and children, were never recaptured during their arduous journeys. Tubman’s success can be attributed to various factors, including her resourcefulness and unwavering determination. Her understanding of ecological dynamics played a crucial role in her ability to outsmart her pursuers and facilitate successful escapes.

Harriet Tubman’s story demonstrates the profound connection between African Americans and the outdoors, challenging conventional perceptions that confine them to the cotton fields of the Southern plantations. Nature provided a sanctuary for these individuals, allowing them to find solace, wisdom, and freedom. Their experiences serve as a testament to the power of nature to shape and inspire the human spirit.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.