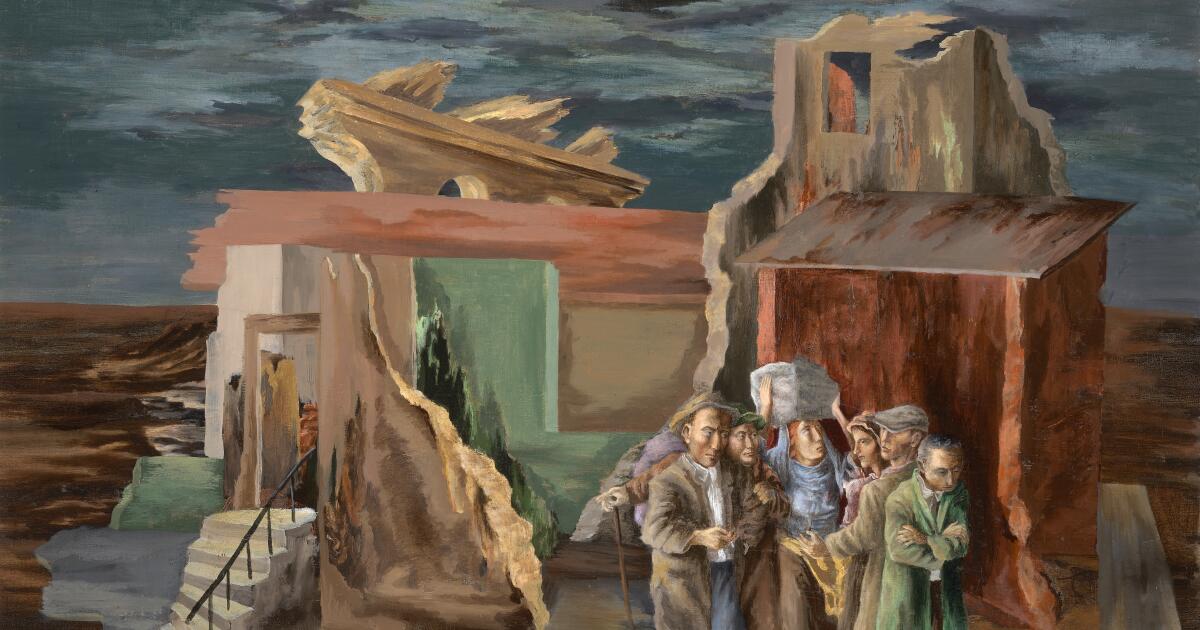

Three men gather around a blazing fire in an oil drum, while an entire community of marginalized individuals goes about their daily routines. From hanging laundry to carrying buckets of water, the dispossessed navigate their difficult lives. Among them, a homeless family desolately stands in front of their wrecked home. Bram Dijkstra comments on the power of these scenes, explaining that despite their vintage appearance, they are reminiscent of the struggles faced in modern society. These thought-provoking paintings, part of what Dijkstra refers to as American Expression, are currently showcased at the Oceanside Museum of Art.

The exhibition, titled “Art for the People: WPA-Era Paintings from the Dijkstra Collection,” made its debut earlier this year at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. It will be on display in Oceanside until November 5th, and then be transferred to the Huntington Library in San Marino from December 2nd to March 18th.

While Dijkstra’s observation about the relevance of these images to today’s America is accurate, it’s unlikely that the artists behind them would receive government support in the present day. Conservative Republicans, who often reject art that questions American capitalism or portrays an underclass, would not endorse such funding. Similarly, Democrats beholden to wealthy donors may not prioritize fighting for government funding to support these types of artworks.

Dijkstra and his wife, Sandra, built their collection through a serendipitous process, stumbling upon pieces in various locations. One day, they discovered a 1928 social realist portrait by Hungarian artist Hugo Gellert, depicting a strong laborer wielding an iron wrench, hanging in a secondhand bookstore in Long Beach. This chance encounter sparked their journey in collecting. (Disclosure: Sandra has been my literary agent for nearly two decades.)

Many of the artworks in the collection were created by artists who flourished during the 1930s and 1940s but faded into obscurity as the artistic trends in the United States shifted away from their humanistic approaches to abstract modernism. Nonetheless, through programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which employed over 8 million unemployed Americans to build infrastructure and create public works, these artists found support.

Harry Hopkins, the head of the WPA, had a deep understanding of poverty and devoted himself to aiding the dispossessed. He fiercely defended and expanded the program against any criticism. The amalgamation of arts programs known as Federal One played a significant role within the WPA. Painters, sculptors, musicians, writers, and theater artists were all beneficiaries of this cultural initiative.

The Dijkstra collection, when viewed as a whole, tells a powerful narrative of suffering during the Great Depression. Art historian Henry Adams, one of the exhibtion catalog’s co-authors, notes that the American artists who are typically revered from that period, such as Grant Wood and Georgia O’Keeffe, neglected or even disdained the themes of suffering that these artists captured. It was often outsiders, immigrants, and Jewish artists who offered fresh perspectives on American hardships.

Racial discrimination, poverty, and the struggles of manual and factory labor were experiences shared by many Americans during that era. Through their artwork, WPA artists communicated the universality of these experiences. Harry Sternberg’s “Coal Miner and Family” (1938) portrays a miner toiling underground while his emaciated family waits above amid debris and ruined homes. William Ashby McCloy’s 1936 piece “Lost Horizon” can be seen as a response to Grant Wood’s famous “American Gothic,” depicting a farming couple defeated in a barren, dust-bowl landscape.

One standout work in the exhibition is Charles White’s 1944 painting “Soldier.” In this piece, a solitary figure stands under a menacing sky, clutching his rifle, embodying existential dread and despair. White, who was drafted at the age of 26, sought to counter the optimistic propaganda surrounding America’s involvement in World War II.

The exhibition showcases not only somber depictions of the working class but also uplifting artworks celebrating California’s natural beauty and urban marvels. One example is Miki Hayakawa’s painting featuring pink peonies in the foreground and a view of San Francisco’s Telegraph Hill and Coit Tower. Emanuel Romano, an Italian-born artist, illustrates solidarity and teamwork among construction workers in his 1941 piece named “Construction Workers: Solidarity in Action.”

Backlash against programs like the WPA was primarily driven by political motives. Critics questioned why the government should finance cultural projects instead of more tangible infrastructural developments. The conservative opposition disapproved of socially conscious themes in art and targeted the leftist and immigrant backgrounds of many artists. Attacks on the WPA reached a climax in 1947 when the State Department canceled a planned international exhibition due to public outrage.

Ultimately, the WPA lost support, and its cultural programs were dismissed. In 1943, the agency auctioned off its entire inventory, selling bundles of paintings to a junk dealer for a mere four cents per pound. Luckily, the canvases found their way into the hands of artists, experts, and dealers who recognized their value.

After the war, the focus of artists and patrons shifted towards abstract art. As Dijkstra explains, “Abstraction was supposed to be the great thing of the moment” as it allowed for purely visual appreciation without the burden of conveying specific content.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.