During my freshman year at Alabama A&M University, I found myself overwhelmed with homework and in need of a change of scenery. Foster Hall was getting too monotonous, so I decided to explore the library at the University of Alabama at Huntsville, which offered longer hours of operation. Making my way across town, I was immediately struck by the stark differences between the two institutions. A&M, founded in 1875 to provide education to Black students who were excluded from American higher education, was a place I held close to my heart. However, I couldn’t help but notice the shortcomings it had. The classroom heaters were always malfunctioning, and the campus shuttle had a tendency to run late during the coldest times. UAH, on the other hand, appeared modern and vibrant, with its new buildings and picturesque fountains. As I walked through the library’s aisles, I discovered books and magazines I had never even heard of before, including the one I now contribute to.

It was on that day, more than a decade ago, that I was confronted with the harsh reality of the two-tiered system in American higher education. One track catered to the privileged with ample resources and social recognition, while the other, predominantly treaded by Black students, lacked those privileges.

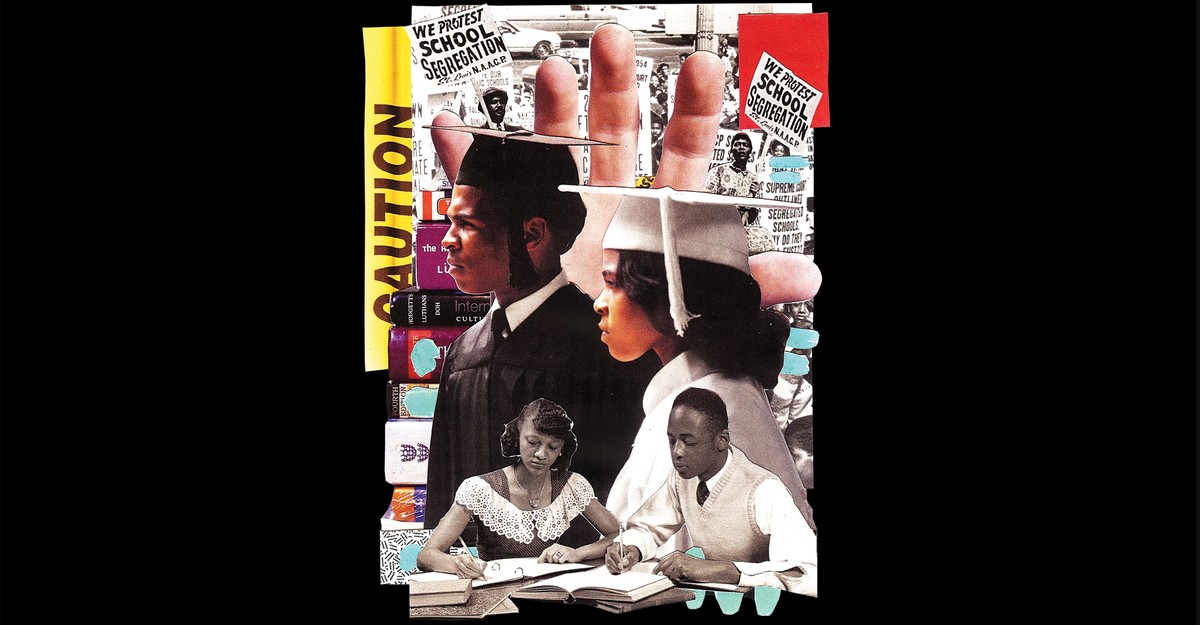

Since its inception, the United States has hindered the progress of Black education. In Alabama during the 1830s, teaching a Black child could result in a hefty fine of $500. The subsequent era of segregation further entrenched discriminatory practices, starting with societal customs and later enforced by state laws. Black educators took matters into their own hands and established their own colleges, but as a 1961 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights revealed, these institutions suffered from chronic underfunding. The report urged for increased federal funding for institutions that did not discriminate against Black students, but little action was taken.

However, with the rise of the civil rights movement, predominantly white institutions began to confront their exclusionary past and implement affirmative action policies. This strategy aimed to give Black students an equal opportunity for higher education. President John F. Kennedy’s executive order in 1961 paved the way for affirmative action by emphasizing diversity in the federal workforce and addressing the historical discrimination faced by applicants of color.

Unfortunately, affirmative action faced numerous challenges from the outset. White applicants filed lawsuits claiming that any consideration of race in hiring or education amounted to discrimination against them. This initiated a gradual erosion of the power of affirmative action to rectify historical injustices. Today, race-conscious admissions policies are limited in scope and only utilized by a handful of highly selective programs. Paradoxically, racial stratification has worsened in many regions.

For instance, in Mississippi, nearly half of high school graduates are Black, but the University of Mississippi’s freshman class in 2019 comprised only 10 percent Black students. The proportion of Black students at the university has steadily declined since 2012. Similarly, Alabama has one-third of high school graduates identifying as Black, yet Auburn University, one of the state’s prestigious public institutions, had a mere 5 percent Black student enrollment in 2019. Despite overall enrollment growth, Auburn now has fewer Black undergraduates than it did in 2002. A report by the nonprofit Education Trust reveals that the percentage of Black students has dwindled at nearly 60 percent of the “101 most selective public colleges and universities” over the past two decades.

The Supreme Court is poised to hear a case, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which could mark the definitive end of affirmative action in higher education nationwide. If the Court takes up the case, the plaintiffs will argue that race should never be a consideration in college admissions. Observers believe that the conservative majority on the Court might sympathize with this view.

Should affirmative action be dismissed, the United States would have to confront the undeniable reality that its higher education system has always been inherently unequal. In order to grasp the consequences of abandoning race-conscious admissions, it is crucial to understand what affirmative action achieved, as well as its limitations.

In 1946, President Harry Truman commissioned a comprehensive report on American higher education. The report revealed that 75,000 Black students were enrolled in colleges across the country, with approximately 85 percent attending underfunded Black institutions. The disparity in funding between white and Black institutions was staggering, ranging from 3 to 1 in the District of Columbia to 42 to 1 in Kentucky.

Affirmative action played a vital role in increasing Black enrollment at predominantly white colleges and universities. The number of Black graduates skyrocketed, more than doubling from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s. However, progress in higher education reform began to stagnate, and by the end of that period, it was running on fumes.

The Bakke case dealt a significant blow to affirmative action. In 1973, Allan Bakke, a white applicant, was rejected by the UC Davis School of Medicine and subsequently sued, arguing that the program’s consideration of race violated his rights. The California Supreme Court ruled in his favor, prohibiting colleges from considering race in admissions. The Supreme Court’s decision in Bakke v. University of California was split, with Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. casting the deciding vote. Powell’s opinion compromised by allowing institutions to consider race for the sake of diversity. Affirmative action, in his view, was not about rectifying historical injustices but about achieving a diverse student body, benefiting all students.

Subsequent court rulings have upheld Powell’s rationale, resulting in cautious affirmative action programs that have failed to make a significant impact. Schools have been hesitant to design comprehensive programs addressing discrimination or systematically increasing Black representation. Only a few rare cases have managed to maintain or slightly improve the proportion of Black students in their student bodies.

While the neutered version of affirmative action may have had some positive impact, its removal would force society to confront the stark disparities in the higher education system. It would unveil the truth about American higher education, revealing the underlying challenges that have persisted. The loss of affirmative action would have far-reaching implications, requiring a collective endeavor to address and rectify the deep-rooted inequalities that persist.

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.