On the last fateful morning of Shinzo Abe’s life, the former prime minister arrived in the historic city of Nara, known for its ancient pagodas and revered deer. However, he wasn’t there to bask in the city’s architectural wonders; instead, he was headed to a bustling urban intersection opposite the main train station. It was at this unremarkable location that Abe would deliver a speech endorsing a lawmaker running for reelection to Japan’s parliament, the National Diet. Despite having officially retired two years earlier, Abe’s name still carried immense weight due to his tenure as Japan’s longest-serving prime minister. The date was July 8, 2022.

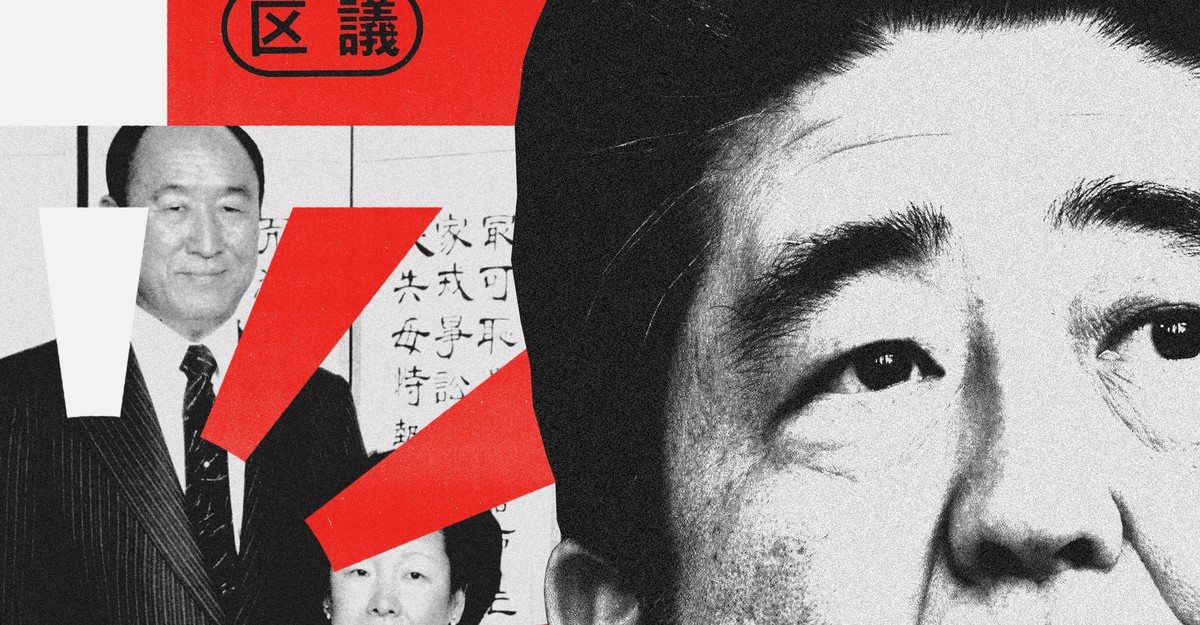

In photographs captured from the lively crowd, Abe stood out with his trademark wavy, swept-back hair, charcoal eyebrows, and warm, folksy smile. At around 11:30 a.m., he mounted a makeshift podium, gripping the microphone with one hand. A group of fervent supporters surrounded him, wholly absorbed in the moment. Yet, amidst the commotion, there was one man, positioned about 20 feet behind Abe, who defied the atmosphere. Dressed casually in a gray polo shirt and cargo pants, with a black strap slung across his shoulder, this individual stood apart from the clapping masses.

Abe began his speech, but his words were abruptly cut short by the sound of two loud reports, immediately followed by a cloud of thick white smoke. In an instant, he crumpled to the ground. Startled, his security guards sprang into action, swiftly converging on the man in the gray polo shirt. This suspect, later identified as 41-year-old Tetsuya Yamagami, made no attempt to flee. Clutched in his hands was a homemade gun, an assemblage of two 16-inch metal pipes secured together with black duct tape. As the guards lunged at him, the gun skittered across the pavement, leaving Yamagami defenseless. Meanwhile, Abe, struck in the neck by a bullet, was fighting for his life, though his fate was sealed; he would succumb to his injuries within a matter of hours.

Shortly after firing the fatal shot, Yamagami found himself at a local police station, where he astonishingly admitted to the crime just half an hour after perpetrating it. However, the motive he provided seemed far-fetched and outlandish: he claimed that he viewed Abe as an ally of the controversial Unification Church, widely known as the Moonies and founded by the Korean evangelist Reverend Sun Myung Moon in the 1950s. Yamagami went on to explain that his life had been irreparably destroyed when his mother bequeathed the entirety of their family’s wealth to the church, leaving Yamagami and his siblings destitute and often hunger-stricken. Tragically, his brother had already succumbed to suicide, while Yamagami himself had even attempted to take his own life.

According to an account published in January by The Asahi Shimbun, Yamagami confessed to the police, stating, “My primary target was the Unification Church’s top official, Hak Ja Han, not Abe.” Naturally, he harbored resentment toward the church, which he believed Abe to be intricately linked to, just as Yamagami’s own grandfather, a prominent political figure in Japan, had been.

Upon investigating Yamagami’s seemingly far-fetched assertions, the authorities were alarmed to realize that there was truth to his claims. In a hasty internal discussion, it was decided that exposing the Moonie connection would be too sensitive at that moment, as it could potentially influence the upcoming Upper House elections scheduled for July 10. During a press conference on the night of the assassination, a police official only alluded to Yamagami’s attack as an outcome of his “animosity towards a particular group, assuming that Abe was associated with it.” When pressed for further details by journalists, the official remained tight-lipped.

Following the elections, the Unification Church verified the press reports by confirming that Yamagami’s mother had indeed been a member. Subsequently, the scandal quickly gained traction, revealing that the Moonies maintained a covert army of campaign workers who were instrumental not just in Abe’s political career but also for numerous other politicians within his conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which still wielded power under Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. In September 2022, the LDP shocking announced that almost half of its 379 Diet members had disclosed some involvement with the Unification Church, ranging from receiving campaign assistance, paying membership fees, or attending church events. A survey conducted by The Asahi Shimbun further unveiled that 290 members of prefectural assemblies, along with seven prefectural governors, also claimed to have associations with the church. These staggering revelations exposed an utterly scandalous reality that had remained cloaked in plain sight: a right-wing Korean cult had a clandestine grip on the political party that had governed Japan for nearly seven decades.

Understandably, the Japanese public was incensed not only by the appearance of bribery and corruption but also by the staggering hypocrisy of it all. Abe, revered by some as a nationalist instrumental in reinstating Japan’s global influence and unabashedly unapologetic for the country’s imperial past, now found himself squarely entangled with a secretive cult that, as later came to light, preyed on Japanese war guilt to extract billions of dollars from vulnerable followers.

As news of Yamagami’s personal history and the LDP’s involvement spread, a startling reversal of sentiment occurred. People began sympathizing with the alleged assassin and directing their anger toward the victim. A Japanese weekly even devoted an entire cover story to Yamagami’s adoring fans, dubbing them the “Yamagami Girls” and highlighting other supporters. Well-wishers showered Yamagami with gifts, while thousands of protesters vehemently opposed the decision to hold a state funeral for Abe. In response to the mounting outrage, a hastily produced feature film painted Yamagami as a tragic hero and was screened throughout the nation. The LDP’s declining poll numbers plummeted even further, leading to the resignation of a cabinet minister who failed to adequately explain his own ties to the church.

In the wake of Abe’s assassination, deep divisions emerged surrounding his legacy. Some lauded him for revitalizing Japan’s global standing, while others vehemently denounced him as a perilous throwback to the nation’s bellicose past. The influence wielded by the Moonies over Abe and the LDP remains an unresolved issue. In November, the Kishida government, eager to clear its name of any association with the cult, initiated an inquiry that could potentially jeopardize the Unification Church’s legal status in Japan as a recognized religion. This significant development, if pursued, may deal a lethal blow and call into question the role of the church in the other countries worldwide where it maintains a presence, including the United States. Essentially, by not charging the group’s leaders with any criminal wrongdoing, the Japanese government would be asserting its authority to determine when a religious organization does more harm than good.

It is highly probable that all of these revelations would have remained concealed were it not for the desperate actions of a man who had found little success elsewhere in life. As Tetsuya Yamagami awaits trial in the solitude of his prison cell, he may find solace in contemplating that he is potentially one of the most successful assassins in history. A full year after Abe’s demise, his murder no longer appears as a random act perpetrated by a deranged loner; rather, it is increasingly viewed as a tragedy that quietly unfolded over the course of several decades.

In the aftermath of Abe’s assassination, many were astonished to discover that the Moonies still held relevance. In both Japan and the United States, the group had receded from the public eye since the 1980s and 1990s, when their unusual mass weddings, eerie totalitarian style, and audacious attempts to exert political influence—such as Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s establishment of The Washington Times, a conservative newspaper in the United States capital—commanded attention.

Another startling revelation was Japan’s pivotal role in Moon’s endeavors. Though the Unification Church is headquartered in South Korea, the majority of its funding, as well as many of its most devoted followers, hail from Japan. Masaue Sakurai, a former high-ranking church official who parted ways with the organization in 2017, provided insight into this matter. In an interview, Sakurai explained that “Japan is actually designated as a core pillar” for the church’s financial operations. Throughout my investigation into the Moonies in Japan, I conversed with roughly a dozen present and former members, their families, as well as lawyers, journalists, politicians, and activists. Among them, Sakurai was the sole individual who displayed a degree of sympathy for both those who vehemently opposed the church and those who revered it. We sat down in a tranquil Tokyo coffee shop, where the gentle strains of Mozart and Schubert piano sonatas filled the room, underscoring the complexity of the situation.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.