The question of “What is art?” and the request to attend a one-person show are both pretentious and infamous. As a writer anticipating the rise of ChatGPT, I cannot escape the need to answer the former. Many people, including writers themselves, often forget that creative writing is indeed an art form. This oversight may be attributed to the fact that writing is something nearly everyone does and believes they do well, unlike music, painting, sculpture, or dance, which require natural talent that distinguishes practitioners from mere appreciators.

During social gatherings, I have encountered friends who are dancers, comedians, visual artists, and musicians, and never have I heard someone say, “I’ve always wanted to do that.” However, it seems that every stranger I meet mentions their unfulfilled desire to write a novel. They believe that the only thing stopping them from writing their magnum opus is a lack of time, not a lack of talent or skill. Yet, similar to how most people are unable to dance en pointe, most people cannot successfully pen a novel. They overlook the fact that writing is an art.

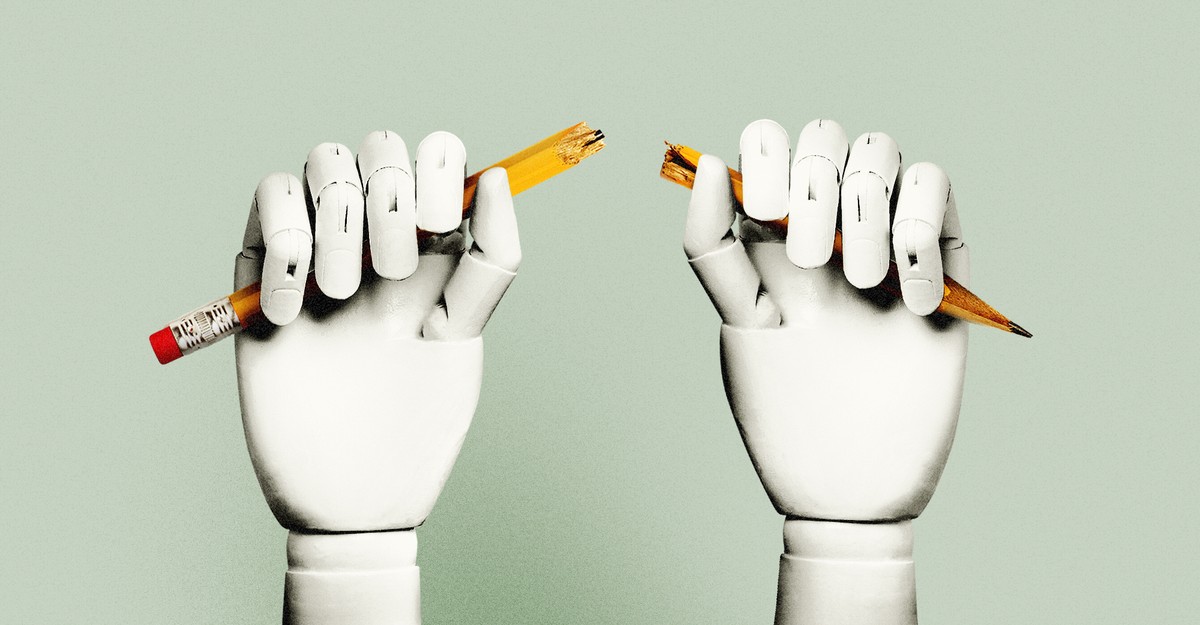

Art delves into the depths of human experience, capturing and distilling emotions. This is a formidable task that can only be accomplished by human beings. That being said, it does not imply that everything produced by humans is effective or good art, nor does it mean that a computer cannot generate content that entertains or informs. However, a computer by itself cannot create art—it can, however, potentially produce “good writing.”

The emergence of ChatGPT forces us to ponder the distinction between art and good writing, often referred to as “craft.” For many writers, the path to publication involves participation in writing-preparatory programs such as workshops, private classes, and M.F.A. programs, all centered around mastering the craft of writing. However, if we desire human writing to continue existing as both an art and a profession, these programs must reassess their priorities in light of the existential crisis they face.

I was 41 years old when I attended my first intensive writing course, a week-long summer workshop. It followed the same pedagogical model as most M.F.A. programs, with an instructor-led workshop where we evaluated each other’s stories, complemented by discussions on craft. The course immensely improved my writing, leaving me hungry for more. Within a year, I enrolled in a master of fine arts program.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time in graduate school. I had instructors who transformed my perception of writing, art, and my identity as an artist. However, I occasionally found myself frustrated, especially during one incident in my final semester. It was the midst of the pandemic, and we were workshopping a classmate’s story that everyone agreed was not “working.” During our Zoom session, we beat around the bush, but in our private chat, some of us were more candid. We felt that the author was evading the true reason their character seemed distressed. In simpler terms, the story was a well-written pile of emotional dishonesty.

Discovering emotional deception within a story feels reminiscent of encountering a well-articulated but feeble excuse in real life—you might accept it, but you’re not convinced. However, the professor’s advice focused on fixing the perspective and adding more action, essentially suggesting mechanical solutions for an emotional problem. Perhaps it was the toll of endless Zoom meetings or my impatience that often accompanied life post-40, but I suddenly unmuted myself and blurted out, “Is this a master’s in fine arts or a master’s in fine mechanics? While the sentences may be flawless, they won’t fix the underlying issue of the story lacking honesty.”

To my surprise, my professor responded, “What’s wrong with being a good mechanic?”

Of course, the answer is nothing. Writing beautiful, lucid sentences that weave together into elegant paragraphs and narratives requires discipline, discernment, and technical proficiency. My work as a novelist has undoubtedly benefitted from the development of my technical skills. However, literary art is not just about the mechanics of language—it’s about how those sentences support emotional truth.

One can dissect excellent writing without ever analyzing or discussing the emotions it entails or evokes. This approach may provide craft strategies to incorporate into one’s own work, a feat that a machine can also accomplish. It can read—indeed, it has read—the same masterful writers that I have. Soon enough, it will likely possess the ability to produce what many M.F.A. programs would consider “good writing.” However, if this new technology saturates the world with such writing, it may render it obsolete.

If we desire to safeguard the art of writing from the reach of computers, writing workshops must go beyond asking, “How could this piece be improved?” and delve into questions like, “How could this piece be more genuine? More emotionally impactful? More resonant?” These questions are tougher, not only due to their subjectivity but because they demand skills that surpass language proficiency: insights into human nature, imagination, innovation, creativity, and mastery of pathos, ethos, and logos. Teaching these aspects is challenging, but it’s worth a try.

Perhaps part of the problem lies in literary-fiction writers overlooking the lessons that mass-market novels can impart. These books may not always showcase masterful writing, but they undoubtedly tap into human experiences and stir emotions, as evidenced by the weeping readers on BookTok. Take Colleen Hoover, for instance, who self-published for years before her romance and young-adult novels became bestsellers. While some critics argue that her books heavily rely on trauma narratives—an accusation that has recently been leveled against certain literary fiction as well—readers continue to devour her stories because they connect with the tales of women finding love in the face of financial collapse or seeking to break free from patterns of domestic violence. You can comment on her sentence construction, but no Colleen Hoover fan believes that ChatGPT can replace her.

To be fair, the best writing instructors have long encouraged students to write with emotional honesty, even before artificial intelligence posed a threat. The most significant lesson I learned about the art of memoir was to write the story I felt, not a mere account of what occurred. A science fiction course taught me that complex human emotions are sometimes best conveyed through realms outside reality. A workshop on novels introduced me to the idea of the author as a maestro, guiding readers through an emotional journey with various movements and variations.

Despite all of this, I am unsure if writing as an art can truly be taught. Without a doubt, one can hone their skills and acquire greater mastery of the craft. However, the intangible elements that make great literary artists who they are cannot be manufactured or replicated, at least not within the confines of a classroom. Perhaps they can only be cultivated through lived experiences and keen observations in the wild world.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to attend a solo performance.

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.