We may typically associate hearing voices with neurological conditions like schizophrenia. However, it has been discovered that under certain conditions, most brains can be tricked into hearing voices that do not actually exist.

A team of researchers from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland and the University Savoie Mont Blanc in France embarked on a study to explore how auditory-verbal hallucinations (AVH) can be triggered in the mind. AVH refers to the phenomenon where individuals hear voices without any speaker present.

Prior research suggests that these hallucinations can arise from either an inability to correctly distinguish oneself from the surrounding environment or from strong beliefs and preconceptions that overpower actual sensory information. The team aimed to test both of these hypotheses.

“Here, we developed a new method of inducing AVH in a controlled laboratory environment by integrating methods from voice perception with sensorimotor stimulation, allowing us to investigate the contribution of both major AVH accounts,” state the researchers in their published paper.

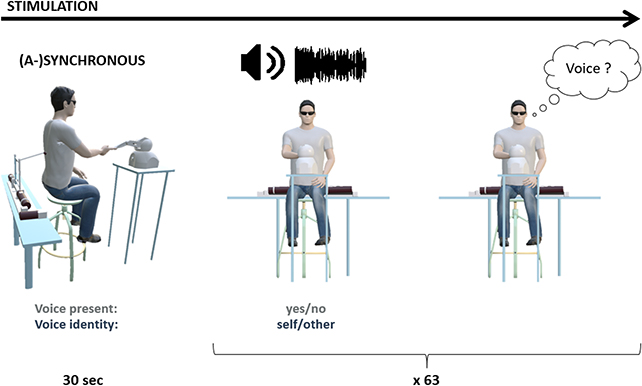

The researchers adapted a technique they had previously employed, where participants poked a button in front of them, and a robotic arm responded by poking them in the back. In this new experiment involving 48 participants, the delay between the button press and the arm poke varied, and the volunteers wore headphones playing a mix of pink noise (resembling the sound of a waterfall) and occasional snippets of voices, including their own and other people’s voices.

Similar to the previous push-button test, the participants reported sensing a presence behind them due to the poking action. However, some of them also reported hearing voices through the headphones that were not actually present.

The occurrence of auditory hallucinations was more frequent when the volunteers heard someone else’s voice before hearing their own, and when there was a time delay between the button press and the arm poke. It seemed as though the participants were conjuring up a voice to associate with the sensation of someone standing behind them.

Based on these findings, the researchers conclude that both theories about the triggers of hallucinations are valid. The participants were not effectively monitoring their environment, and their strong beliefs about their surroundings influenced their perception.

Furthermore, the frequency of hallucinated voices increased as the duration of the tests progressed. Towards the end of the experimental session, participants were more likely to experience the phantom sounds.

Understanding the triggers of these hallucinations is crucial for comprehending their connection to conditions such as Parkinson’s disease. It is also an indication that hearing a voice in one’s head may not necessarily be cause for immediate concern (though seeking medical advice is advisable if there are any worries).

“In addition to the novelty and significant methodological impact, these results provide new insights into the phenomenology of AVH, offering experimental support for both prominent and seemingly contradictory explanations. They depict AVH as a combination of deficits in self-monitoring and hyper-precise priors,” the researchers write.

The research findings have been published in Psychological Medicine.