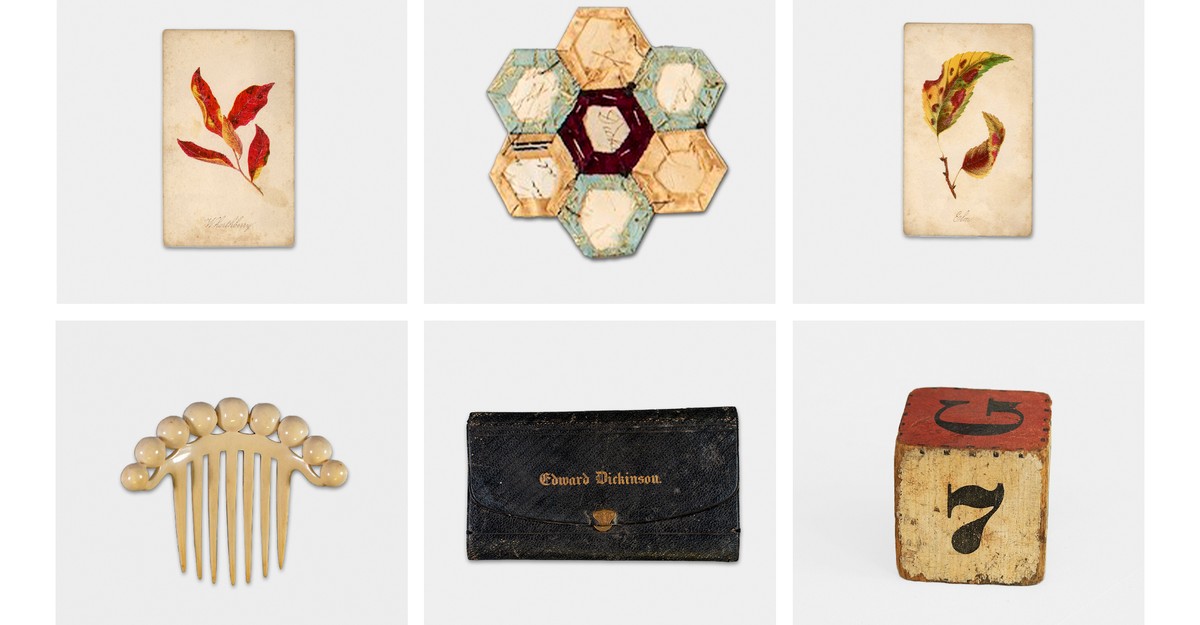

Few American writers have a more intimate connection to a single house than Emily Dickinson. The reclusive poet rarely ventured far from her residence in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she penned nearly 2,000 poems. Despite only a handful being published during her lifetime, the house, known as the Dickinson Homestead, served as the epicenter of her creative imagination. Recently, the Emily Dickinson Museum released a public database cataloging over 8,000 family objects, meticulously assembled and stored in a secretive warehouse in Western Massachusetts. However, this extraordinary collection conceals a convoluted and bitter saga surrounding its preservation.

Following Dickinson’s death in 1886, her sister, Lavinia, began to clean out the poet’s belongings in the Homestead. To her astonishment, she stumbled upon numerous sheets of verse hidden away in a bureau drawer. Although the family was aware of Dickinson’s poetry and her correspondence with several writers and editors, they were clueless about the enormity of her poetic output. Seeking assistance in sorting through the verse for publication, Lavinia turned to Susan Dickinson, her sister-in-law. Having delayed her involvement, Susan’s procrastination frustrated Lavinia.

Desperate for help, Lavinia approached Mabel Loomis Todd, a neighbor and the wife of an Amherst College astronomy professor. Todd, an ambitious individual with artistic inclinations, agreed to lend a hand. She enlisted the support of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a renowned writer who had a longstanding mentorship with Dickinson. Together, they worked on transcribing the poems, making editorial decisions, adding titles, and organizing the verse thematically. In 1890, Todd and Higginson published the first volume of Dickinson’s poetry, introducing her to the world. Unfortunately, their actions enraged Lavinia and Susan, as Todd refused to return Dickinson’s manuscripts and kept them in her possession for future editions. This resistance was unsurprising, given that Todd was secretly involved in a romantic relationship with Susan’s husband, Austin Dickinson, resulting in a longstanding conflict.

Both Mabel Todd and Susan held onto the manuscripts they possessed and refused to relinquish them. After Austin’s death in 1895, followed by Lavinia’s passing, and the deaths of Dickinson’s surviving nephews, Martha Dickinson became the sole descendant of the family and the custodian of the Homestead and the Evergreens, along with all their contents. However, Martha had her own literary ambitions and felt constrained by her familial obligations. She reluctantly took on the task of organizing her aunt’s verse. Martha, who had once referred to herself as “forced to become a niece,” longed to be recognized as a writer.

The management of the Homestead and the Evergreens proved to be challenging for Martha. In 1902, while in Bohemia, she married Alexander Bianchi, a man claiming to be a count and a captain in the Russian Imperial Horse Guards. Calling herself Madame Bianchi, she returned to Amherst with her husband, only to face his mounting debts and deceit. Martha divorced him and narrowly avoided losing the Dickinson properties to creditors. In a bid for financial stability, she sold Emily Dickinson’s home and moved all the family possessions across the lawn to the Evergreens. Dickinson’s belongings remained unsorted.

Eventually, Martha realized she needed assistance with reviewing her aunt’s literary manuscripts, especially as she desired to publish her own editions of Dickinson’s work. After forming a friendship with Alfred Hampson, a professional tenor from the National Arts Club in New York City, Martha sought his aid. The two dug through mountains of material, discovering letters and poems that Dickinson had sent to Susan. Utilizing this fresh material, Bianchi and Hampson edited multiple volumes of Dickinson’s poetry and letters. Nonetheless, they were wary of the possibility of a fire destroying the remaining manuscripts and contemplated offering them to a different archive, excluding Amherst College, where Todd’s collection had found a home.

As Bianchi neared death in 1943, she struggled to determine the fate of the Evergreens. She debated whether to sell it, convert it into a cultural center, or even demolish it. She feared it might become a trivialized establishment, tarnishing the Dickinsons’ legacy. In her final will, Bianchi bequeathed the Evergreens and all its contents to Alfred Hampson, with the instructions to raze the house after his death, ensuring its preservation. Hampson sought advice from a rare-books dealer, leading to the transfer of the Dickinson manuscripts in the Evergreens to Harvard University. Staying true to Bianchi’s wishes, he married Mary Landis, one of her old acquaintances from the National Arts Club. Despite facing challenges like Hampson’s alcoholism and financial troubles, Landis dutifully became the custodian of Emily Dickinson’s legacy.

In her later years, Mary developed a friendship with Barton Levi St. Armand and George Monteiro, two professors from Brown University. Recognizing the historical significance of the Evergreens and its contents, the scholars spent hours discussing the importance of Bianchi in the Dickinson family’s literary legacy. Worried that Bianchi would not receive recognition, Mary dedicated boxes of Bianchi’s correspondence, family photographs, and books to be kept in the special collections at Brown University. She meticulously attached notes to the items, explaining their origin and Bianchi’s description of them. However, despite her reverence for Bianchi, Mary couldn’t bear to tear down the Evergreens.

As Emily Dickinson’s fame soared and the Homestead received visitors after its sale to Amherst College in 1965, Mary realized the growing importance of the Evergreens. When she passed away in 1988, her will contested Bianchi’s, mainly due to the insistence of preserving the Evergreens.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.