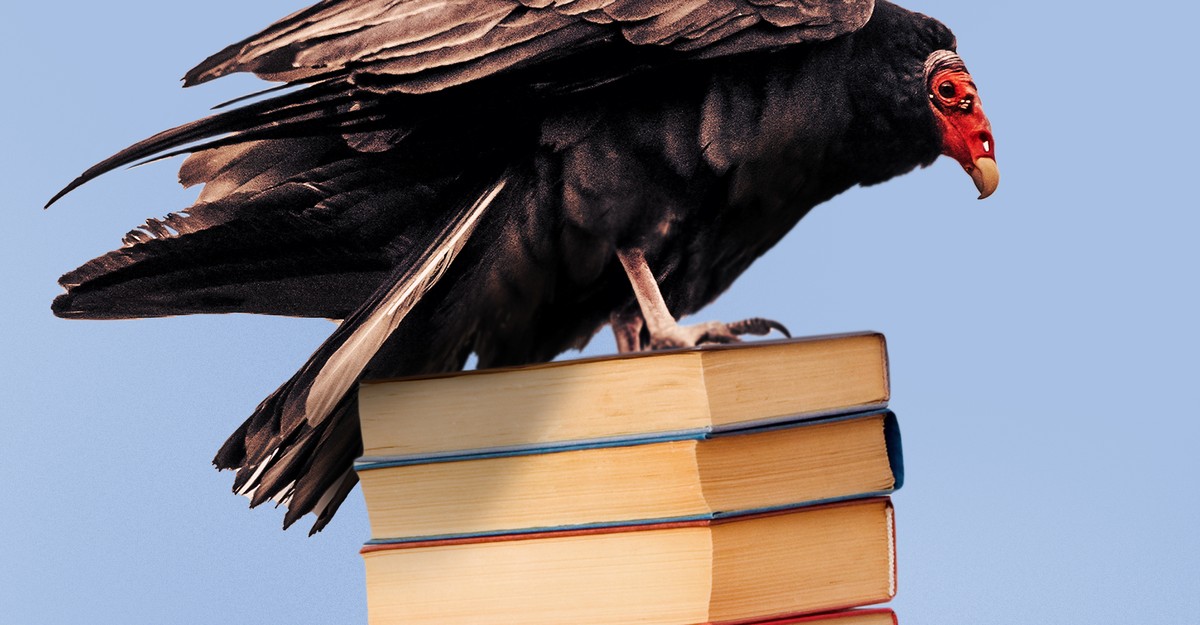

Earlier this year, the Department of Justice prevented Penguin Random House, a company owned by German media giant Bertelsmann, from acquiring Simon & Schuster. HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, Hachette, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster already dominate 80 percent of the book market. The literary community sighed with relief.

Less than a year later, private-equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) announced its intention to purchase Simon & Schuster. This move may not trigger an antitrust probe, as KKR does not currently own a competing publisher. However, the reputation of KKR, notorious as Wall Street’s “barbarians at the gate” in the 1980s, leaves employees and authors of Simon & Schuster yearning for an alternative to a multinational conglomerate or a powerful financial institution.

Ellen Adler, publisher at the non-profit New Press, commented, “It may only be a temporary reprieve, but we should all be concerned about the future of Simon & Schuster in five years.”

On the surface, the Simon & Schuster acquisition seems like a typical private-equity deal, which is precisely the problem. Private equity is the sanitized term for what used to be known as “leveraged buyouts.” KKR’s notorious leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco in 1988, worth $25 billion, contributed to the negative connotations associated with this form of business transaction. In a leveraged buyout, the buyer acquires a company using a small amount of their own funds, a larger amount borrowed from investors, and significant debt. KKR has agreed to pay $1.62 billion for Simon & Schuster, with $1 billion of that amount being borrowed money.

From the perspective of the private-equity firm, leveraging is not a flaw but a feature. If you purchase a company for $100 million in cash without any debt and make an annual profit of $5 million, you will yield a 5% return. However, if you buy the same company using 60% debt, that same profit will yield a 12.5% return in absolute terms.

Crucially, Simon & Schuster, not KKR, is responsible for repaying the debt. KKR raises the debt against the publisher’s franchise value to finance the acquisition, with lenders having no recourse to KKR or its executives. KKR will technically not own Simon & Schuster; instead, a fund that KKR “advises” will be the owner. Moody’s is expected to assign the $1 billion debt a credit rating approximately five levels below investment grade, similar to subprime mortgages.

Based on the terms offered to similarly rated borrowers and our analysis of Bloomberg data on recent transactions, Simon & Schuster will likely face interest rates exceeding 9%. This would cost the publisher nearly $100 million in interest alone, equivalent to 40% of its operating income in 2022. The financial burden of the transaction will weaken Simon & Schuster even before considering KKR’s role as the owner.

Eileen Appelbaum, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and a prominent critic of private equity, warns that high levels of debt place considerable strain on a company. Appelbaum states, “It undermines its ability to invest in technology, marketing, workers, and everything else.”

Private-equity executives argue that the debt is worth it, claiming their business acumen will make the acquisition much more profitable, allowing them to sell it for a substantial profit within a few years. Although KKR has touted plans to expand into new publishing genres domestically and overseas, the typical private-equity playbook involves cutting costs and maximizing cash flow. This approach often leads to worker layoffs and asset sales, benefiting the private-equity firm but not necessarily the acquired company.

Private equity firms have been buying news publications for the past decade, resulting in layoffs of journalists and editors, reduced print editions, and fewer investments in quality journalism. However, these methods may not apply to book publishing. Simon & Schuster does not own its headquarters at Rockefeller Center and only has around 1,500 employees. Furthermore, KKR has stated no layoffs are planned.

Consequently, the new owners may employ other tactics to enhance short-term returns. Dan Sinykin, a professor at Emory University, suggests that KKR could focus more heavily on established authors or celebrity memoirs, neglecting riskier unknown writers. This approach prioritizes established brands as a cost-cutting measure, serving as a substitute for expensive marketing.

Book publishers generate revenue from sales of their original products, with a portion allocated for author royalties. Private equity in publishing sees an opportunity to monetize intellectual property and may put pressure on Simon & Schuster authors to provide a larger share of their earnings to the publisher. Another speculative possibility involves utilizing authors’ original work to train AI models that generate new monetizable content. This prospect raises concerns among authors about potential co-ownership of copyrights with KKR’s Simon & Schuster.

Ultimately, KKR may not need to ensure increased profitability for Simon & Schuster. Like other private-equity firms, KKR can still profit even if the acquired company suffers. The $620 million not covered by debt will come from a fund assembled by KKR, including entities such as state pension funds, a Chinese insurer, and an Icelandic pilots’ union. Eileen Appelbaum predicts that KKR’s share itself could range from 2% to 10%, equivalent to $12.4 million to $62 million. KKR only contributed 0.06% of its own money for the RJR Nabisco takeover.

The company can begin generating cash immediately. Private-equity firms earn “management fees” from their investors and “monitoring” or “advisory” fees from the companies they acquire. KKR and its partners received $185 million in advisory fees from Toys “R” Us before driving it into bankruptcy. With Simon & Schuster, fees alone could allow KKR to recoup its investment within a few years.

Another method of extracting money involves “dividend recapitalization,” a term that effectively means “debt-fueled payouts.” In this tactic, the acquired company issues bonds to raise funds paid out to new owners and used to refinance old debt. Private equity commonly employs this approach. KKR recently extracted $750 million ($385 million for itself) from Atlantic Aviation, leading to a debt load seven times its annual earnings.

KKR has a history documented in Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner’s book These Are the Plunderers of bankrupting Toys “R” Us, exploiting Bayonne, New Jersey residents for their water and sewage needs, and driving an essential emergency services provider into the ground. If KKR follows a similar trajectory with its latest deal, Morgenson and Rosner may have a harder time exposing it. The publisher of their book is Simon & Schuster.

Purchasing a book through the provided links on this page will result in us receiving a commission. We appreciate your support of The Atlantic.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.