The Complex Nature of Digital Privacy and the Importance of Protecting It

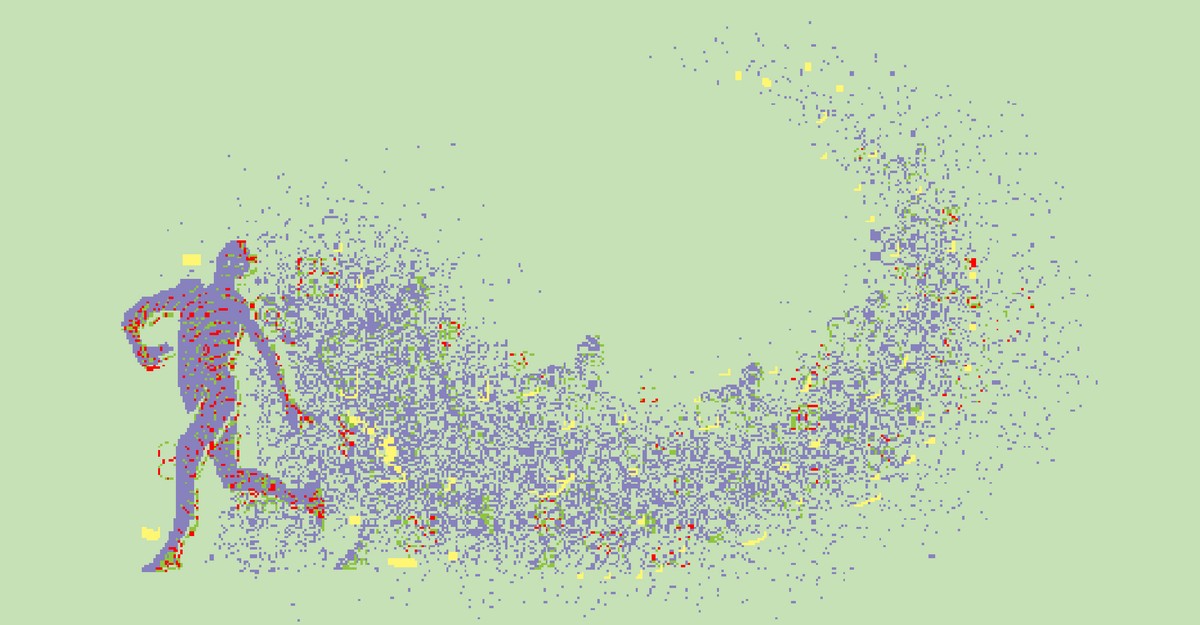

We are all shedding data like skin cells. Almost everything we do with, or simply in proximity to, a connected device generates some small bit of information—about who we are, about the device we’re using and the other devices nearby, about what we did and when and how and for how long. Sometimes doing nothing at all—merely lingering on a webpage—is recorded as a relevant piece of information. Sometimes simply walking past a Wi-Fi router is a data point to be captured and processed. Sometimes the connected device isn’t a phone or a computer, as such; sometimes it’s a traffic light or a toaster or a toilet. If it is our phone, and we have location services enabled—which many people do, so that they can get delivery and Find My Friends and benefit from the convenience of turn-by-turn directions—our precise location data are being constantly collected and transmitted. We pick up our devices and command them to open the world for us, which they do quite well. But they also produce a secondary output too—all those tiny flecks of dead skin floating around us.

Our data are everywhere because our data are useful. Mostly to make people money: When someone opens up their phone’s browser and clicks on a link—to use the most basic example—a whole hidden economy whirs into gear. Tracking pixels and cookies capture their information and feed it to different marketers and companies, which aggregate it with information gleaned from other people and other sites and use it to categorize us into “interest segments.” The more data gathered, the easier it is to predict who we are, what we like, where we live, whom we might vote for, how much money we might have, what we might like to buy with it. Once our information has been collected, it ricochets around a labyrinthine ad-tech ecosystem made up of thousands of companies that offer to make sense of, and serve hyper-targeted ads based on, it.

Our privacy is what the internet eats to live. Participating in some part or another of the ad-tech industry is how most every website and app we use makes money. But ad targeting isn’t the only thing our data are good for. Health-care companies and wearables makers want our medical history and biometric data—when and how we sleep; our respiratory rate, heart rate, steps, mile times; even our sexual habits—to feed us insights via their products. Cameras and sensors, on street corners and on freeways, in schools and in offices, scan faces and license plates in order to make us safer or identify traffic patterns. Monitoring software tracks students taking tests and logs the keystrokes of corporate employees. Even if not all of our information goes toward selling ads, it goes somewhere. It is collected, bought, sold, copied, logged, archived, aggregated, exploited, leaked to reporters, scrutinized by intelligence analysts, stolen by hackers, subjected to any number of hypothetical actions—good and bad, but mostly unknowable. The only certainty is that once our information is out there, we’re not getting it back.

It’s scary and concerning, but mostly it’s overwhelming. In modern life, data are omnipresent. And yet, it is impossible to zoom out and see the entire picture, the full patchwork quilt of our information ecosystem. The philosopher Timothy Morton has a term for elements of our world that behave this way: A hyperobject is a concept so big and complex that it can’t be adequately described. Both our data and the way they are being compromised are hyperobjects.

Climate change is one too: If somebody asks you what the state of climate change is, simply responding that “it is bad” is accurate, but a wild oversimplification. As with climate change, we can all too easily look at the state of our digital privacy, feel absolutely buried in bad news, and become a privacy doomer, wallowing in the realization that we are giving our most intimate information to the largest and most powerful companies on Earth and have been for decades. Just as easy is reading this essay and choosing nihilism, resigning yourself to being the victim of surveillance, so much that you don’t take precautions.

These are meager options, even if they can feel like the only ones available. Digital privacy isn’t some binary problem we can think of as purely solvable. It is the base condition and the broader context of our connected lives. It is dynamic, meaning that it is a negotiation between ourselves and the world around us. It is something to be protected and preserved, and in a perfect world, we ought to be able to guard or shed it as we see fit. But in this world, the balance of power is tilted out of our reach. Imagine you’re in a new city. You’re downloading an app to buy a ticket for a train that’s fast approaching. Time is of the essence. You hurriedly scroll through a terms-of-service agreement and, without reading, click “Accept.” You’ve technically entered a contractual agreement. Now consider that in such a moment, you might as well be sitting at a conference table. On one side is a team of high-priced corporate lawyers, working diligently to shield their deep-pocketed clients from liability while getting what they need from you. On the other side is you, a person in a train station trying to download an app. Not a fair fight.

So one way to think of privacy is as a series of choices. If you’d like a service to offer you turn-by-turn directions, you choose to give it your location. If you’d like a shopping website to remember what’s in your cart, you choose to allow cookies. But companies have gotten good at exploiting these choices and, in many cases, obscuring the true nature of them. Clicking “Agree” on an app’s terms of service, might mean, in the eyes of an exploitative company, that the app will not only take the information you’re giving up but will sell it to, or share it with, other companies.

Understanding that we give these companies an inch and they take a mile is crucial to demystifying their most common defense: the privacy paradox. That term was first coined in 2001 by an HP researcher named Barry Brown who was trying to explain why early internet users seemed concerned about data collection but were “also willing to lose that privacy for very little gain” in the form of supermarket loyalty-rewards programs. People must not actually care so much about their privacy, the argument goes, because they happily use the tools and services that siphon off their personal data. Maybe you’ve even convinced yourself of this after almost two decades of devoted Facebooking and Googling.

But the privacy paradox is a facile framework for a complex issue. Daniel J. Solove, a professor at George Washington University Law School, argues the paradox does not exist, in part because “managing one’s privacy is a vast, complex, and never-ending project that does not scale.” In a world where we are constantly shedding data and thousands of companies are dedicated to collecting it, “people can’t learn enough about privacy risks to make informed decisions,” he wrote in a 2020 article. And so resignedly and haphazardly managing our personal privacy is all we can do from day to day. We have no alternative.

But that doesn’t mean we don’t care. Even if we don’t place a high value on our personal data privacy, we might have strong concerns about the implications of organizations surveilling us and profiting off the collection of our information. “The value of privacy isn’t based on one’s particular choice in a particular context; privacy’s value involves the right to have choices and protections,” Solove argues. “People can value having the choice even if they choose to trade away their personal data; and people can value others having the right to make the choice for themselves.”

This notion is fundamental to another way to think of privacy: as a civil right. That’s what the scholar Danielle Keats Citron argues in her book The Fight for Privacy. Privacy is freedom, and freedom is necessary for humans to thrive. But protecting that right is difficult, because privacy-related harm is diffuse and can come in many different forms: At its most extreme, it can be physical (violence and…

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.