At first, doctors were skeptical about the possibility of bacteria surviving in the stomach due to its high acidity. However, in 1984, a young Australian physician named Barry Marshall conducted an experiment. He consumed a concoction of beef broth mixed with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria. After eight days, he started experiencing vomiting. On the tenth day, an endoscopy revealed the presence of H. pylori in his stomach, easily identifiable with its characteristic spiral shape under the microscope.

If left untreated, H. pylori can lead to lifelong infections, and it is more common than one might think. Over half of the world’s population and more than one in three Americans carry H. pylori in their stomachs. In most cases, the bacteria cause asymptomatic chronic infections. However, in some individuals, it can lead to the development of ulcers and even cancer. In fact, H. pylori is the leading risk factor for stomach cancers worldwide, accounting for approximately 70% of cases.

Even years later, doctors are still puzzled as to why H. pylori has different effects on different people. Why is it harmless in most cases but cancer-causing in others? While the full answer is complex, one significant factor seems to be mutations in the H. pylori bacteria itself. Not all strains of the bacteria are equal. The presence of specific genes increases the bacteria’s pathogenicity, and recent studies have shown that even a single mutation in a single gene can enhance its link to cancer. Therefore, a small genetic change in this common stomach bacteria can have profound consequences for the individuals it infects.

H. pylori has been present in humans for a long time. As our ancestors migrated across continents and oceans, they likely carried the bacteria within them. In a process of co-evolution believed to span over 100,000 years, H. pylori has adapted remarkably well to the harsh and acidic conditions of the human stomach.

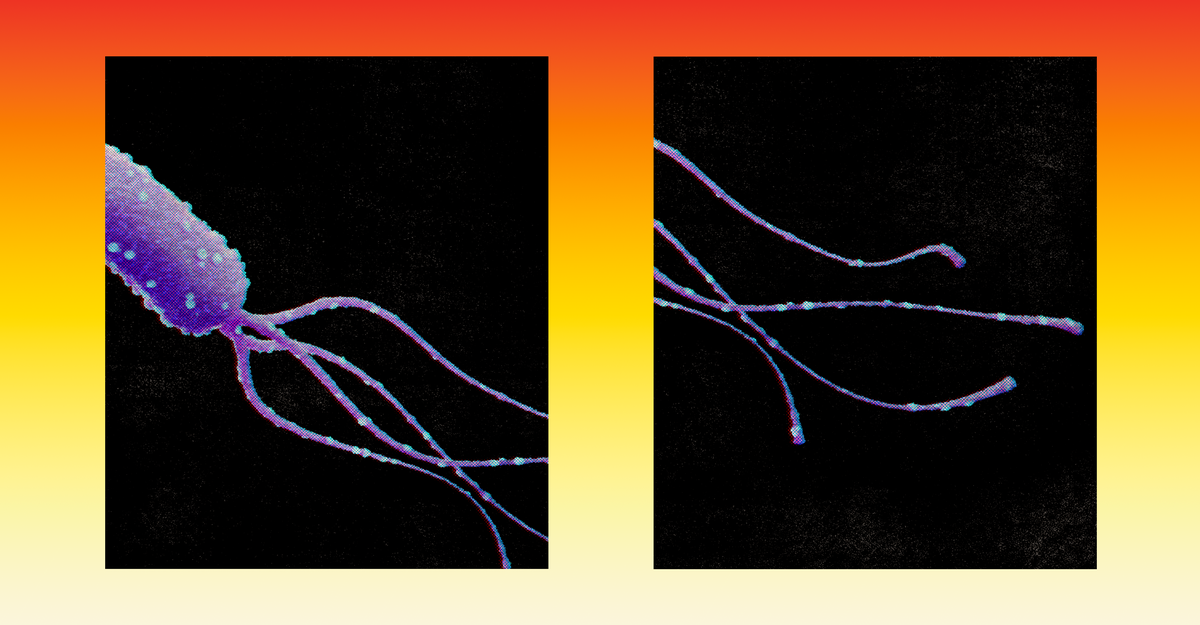

The bacteria survive by producing large amounts of an enzyme that neutralizes stomach acid. It also uses its whiplike flagella to burrow into the protective mucus-gel lining of the stomach, which provides a haven from stomach acid. Beneath this lining lies the prize for H. pylori – stomach cells rich in nutrients that the bacteria needs to sustain itself.

The way H. pylori steals nutrients from stomach cells is believed to be the key to its cancer-causing potential. The bacteria doesn’t intend to harm its human host. Its primary goal is to replicate in high enough numbers to be transmitted to another person. To achieve this, it requires nutrients, particularly iron. However, our cells tend to hoard iron to starve pathogens like H. pylori.

In response, certain strains of H. pylori have evolved genetic changes that enhance their ability to extract iron from cells. Unfortunately, this also causes more damage to the stomach lining, potentially triggering cancer in the long run. H. pylori uses a protein called HtrA, described as “a pair of molecular scissors,” to cut the bonds holding stomach cells together, allowing the bacteria to penetrate between them. Recent research has shown that a single mutation in this protein makes the scissors more efficient at cutting, and this mutation is more prevalent in H. pylori strains isolated from individuals who developed stomach cancer.

Once H. pylori infiltrates cells, it employs clever tactics to access the nutrients within. Certain strains carry about 18 genes known as the “cag pathogenicity island.” These genes encode a molecular needle through which H. pylori injects bacterial proteins into cells, triggering a series of changes. These hijacked cells become more prone to releasing their iron, but they also struggle with essential functions such as DNA repair. Interestingly, these cancer-linked genes are overrepresented in strains isolated from cancer patients. Stomach cancer may, therefore, be a secondary consequence of H. pylori’s aggressive search for nutrients. Karen Guillemin, a microbiologist, explains that the selective pressure for H. pylori is not to cause cancer in 80 years but to acquire iron promptly.

However, not everyone infected with these cancer-linked strains will develop cancer. Other factors, including diet, environment, and an individual’s genetics, likely play a role. Stomach cancer rates vary globally, with the highest prevalence in East Asia. In Japan, doctors regularly test for H. pylori in asymptomatic individuals and prescribe antibiotics if the results are positive. Nonetheless, some scientists argue against aggressive treatment, pointing out potential benefits humans may derive from cohabiting with H. pylori. For instance, infected individuals tend to have lower rates of asthma and allergies. Identifying genetic signatures associated with more pathogenic strains of H. pylori could help identify those at higher risk who could benefit the most from antibiotic treatment.

Dr. Barry Marshall, the Australian physician who infected himself with H. pylori, made a full recovery. His self-experiment, along with the collaborative efforts of Robin Warren, provided conclusive evidence that the bacterium does infect the stomach and cause ulcers. This groundbreaking work paved the way for further research linking H. pylori to cancer. Although understanding the mechanisms behind H. pylori’s pathogenicity is crucial for finding effective treatments, its significance in human health is undeniable. In recognition of their contributions, Marshall and Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2005.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.