The riot that eventually unfolded was not a spontaneous event. Leading up to August 11, 1834, the people of Boston had openly discussed their desire to burn down the Ursuline Convent located near the city, in what is now Somerville. They had convinced themselves that the convent was a hub of sexual immorality, where priests used the confessional as a means of blackmail and manipulation to control young women and coerce them into acts of depravity. Additionally, rumors circulated that infants born from these sinful acts were being murdered and buried in the convent’s basement. The only solution, they believed, was to free the women and calmly destroy the entire place.

The Ursuline convent became the target of these conspiracy theories, reflecting the 1830s version of today’s concerns regarding child sexual abuse, such as the Pizzagate conspiracy theory or allegations made by Operation Underground Railroad and QAnon. While these moral panics may appear to be a new phenomenon, they have actually been a part of American culture for almost two centuries, reappearing during pivotal moments in history for specific reasons. To counteract them, it is important to recognize that they are not novel but rather repetitive and almost mundane.

Conspiracy theories tend to emerge during periods of rapid cultural or demographic change. Many of them stem from unease with this change, suggesting that it is not just the result of evolving values or the emergence of new communities, but rather the work of a hidden network of malicious individuals whose ultimate goal is to destroy America itself. These theories often portray the American nuclear family, especially women and children, as uniquely vulnerable and in need of protection.

In the late 1820s and early 1830s, a significant increase in immigration from Ireland and Germany sparked a rise in anti-Catholic sentiment. Anti-Catholicism was not a new concept; it had been integral to the establishment of American democracy, a model that rejected the authority of a divine figure. Protestants feared that Catholics could not be trusted to participate in representative democracy because they would vote en masse according to the wishes of the pope, rather than as autonomous citizens making informed decisions. This aspect of anti-Catholicism, which focused on the idea that individuals could be controlled by a religious authority not bound by American sovereignty, explains why it has been easily redirected against Muslim immigrants and the fear of Sharia law.

In the mid-19th century, the influx of Catholic immigrants transformed the philosophical question about Catholicism into a more urgent and paranoid one. Being Catholic became a rumor and a slur. Conspiracy theories flourished, often revolving around the perceived threat of white Protestants being enslaved by the pope. These theories aimed to preserve a sense of white unity at a time when the question of actual slavery was fueling national division before the Civil War. Anti-Catholic conspiracy theorists repeatedly used the fear of Catholic mind control to divert attention from America’s internal conflicts. While white individuals disagreed on whether African Americans should be enslaved, they could all agree that they did not want such a fate for themselves.

A new literary genre emerged, with popular books featuring convents as their subject matter. Some claimed to be memoirs, while others were pure works of fiction. They depicted a nightmare world of women in bondage, lecherous priests, and murdered infants buried in cellars. These sensationalist faux memoirs and novels were both scandalous and moralizing, offering a voyeuristic glimpse into a world of forbidden pleasure while simultaneously condemning it. Despite their exaggerated details, they presented a moralistic worldview. For instance, Scipio de Ricci argued that the primary objective of monastic institutions in America was to convert influential young individuals, particularly females, as the Roman priests were aware that this would grant them control over public affairs.

The convent symbolized a space separate from the home, challenging the role of Protestant women as mothers and wives. Although women in the early days of the republic lacked the right to vote, they were portrayed as the guardians of democracy, as it was believed to be their duty to raise virtuous sons. This concept, referred to as “Republican motherhood” by scholar Linda Kerber, illustrated the complex dynamic where women were praised as carriers of American ideals while being denied political power. Consequently, men worried about secretive subversion often expressed concerns about women’s susceptibility to moral decay and assumed that foreign conspirators would target them in their efforts to undermine America.

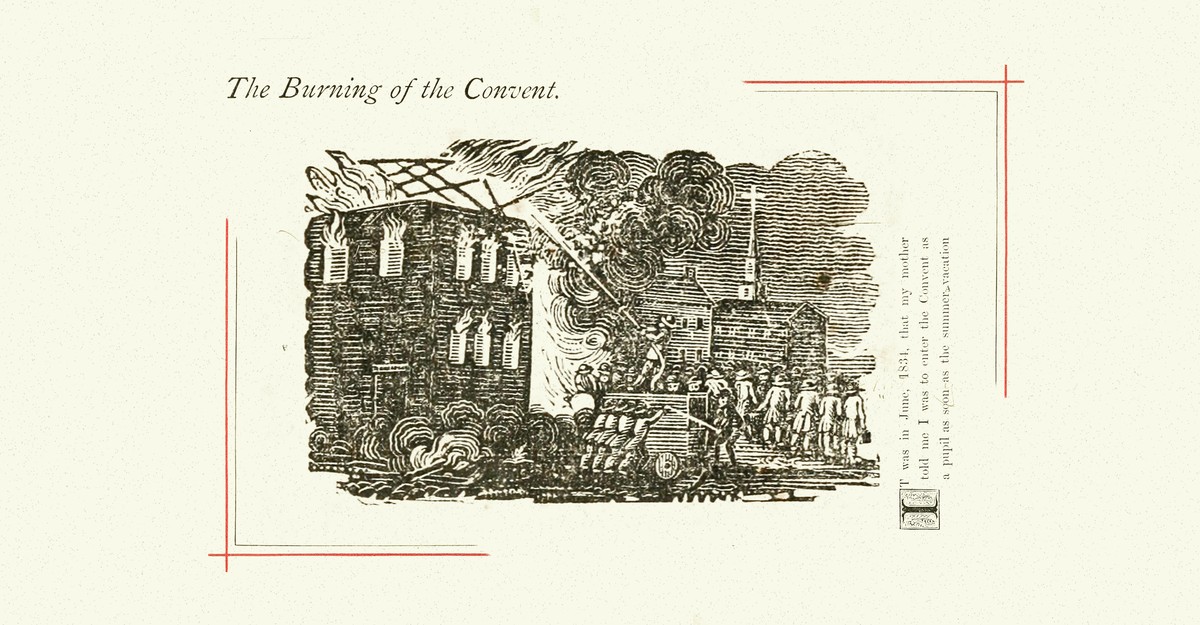

It was only a matter of time before these scandalous rumors and simmering xenophobia erupted into violent actions. The Ursuline convent in Boston had been established in 1820 and quickly became a leading educational institution for both Catholic and Protestant young women from elite families. However, it stood apart from the city center, towering over its predominantly working-class neighbors in Mount Benedict. Tensions between the nuns, particularly the mother superior, Sister Mary Edmond St. George, and the local community were already high. As John Buzzell later remarked about St. George, “She was the sauciest woman I ever heard talk.”

These local tensions were fueled by the growing national anti-Catholic sentiment and the influx of sensationalist books. When Elizabeth Harrison, a music teacher at the convent for 12 years, fled on the night of July 28, 1834, the community saw it as confirmation of their deepest suspicions. Harrison sought refuge with a neighbor before being taken to her brother in Cambridge. She expressed her reluctance to return to Mount Benedict, although the exact reasons were never fully explained. Within hours, the Bishop arrived to console her and tackle the growing unrest.

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.