Stephen Hampton, a seasoned birdwatcher with over 50 years of experience, recently had an epiphany about the names of certain bird species. Previously, these names held no significance to him, as they were simply entries in the bird book he grew up with. However, a few years ago, Hampton discovered the origin of Scott’s oriole, a stunning bird with black and yellow plumage.

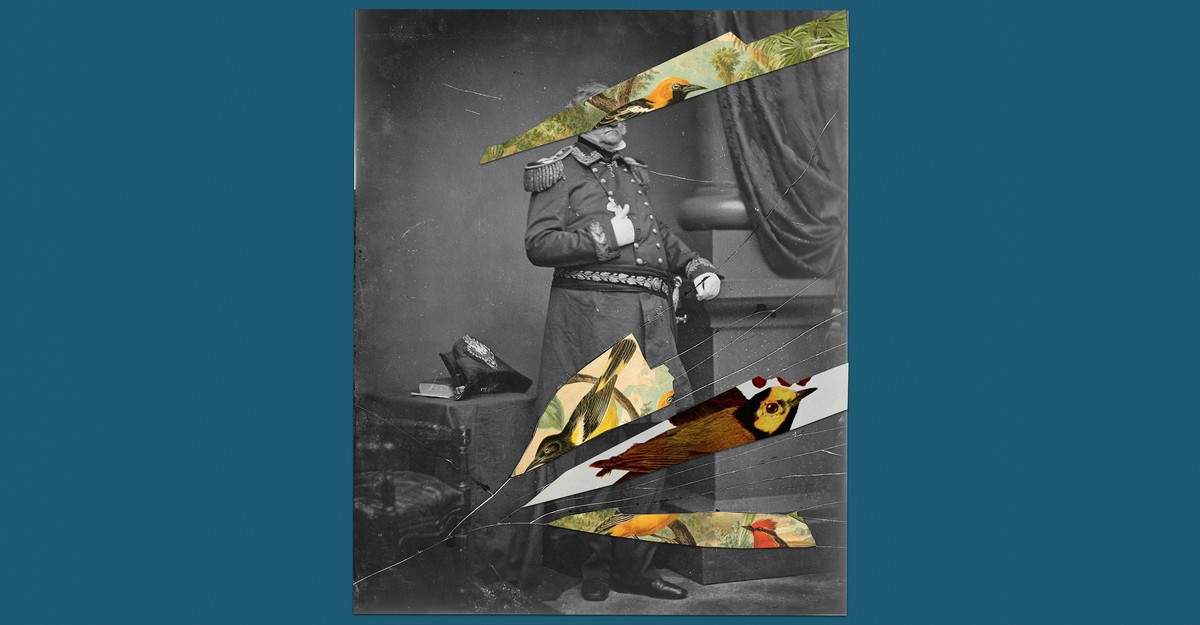

It turns out that Darius Couch, an amateur naturalist and U.S. Army officer, named the oriole in 1854 after his commander, General Winfield Scott. Unfortunately, Scott’s legacy is tarnished by his involvement in the forced removal of the Cherokee people, known as the Trail of Tears. This historical context hit home for Hampton, as his own ancestors were among those forcibly displaced. The name of the bird now deeply affects him on a personal level.

What Hampton uncovered extends beyond Scott’s oriole. In fact, the common names of almost 150 North American birds are eponyms, meaning they are derived from people. These names were often given by soldier-scientists during the early 19th century as a way to honor commanders, benefactors, and family members. However, many of these individuals were also tied to acts of conquest and colonization. This has led many birders to advocate for the removal of these eponyms, as they believe they link the joy of birdwatching to humanity’s dark and oppressive history.

Similar movements for change are taking place in other countries and animal groups. Several animals, whose names previously included ethnic and racial slurs, have been given new, more respectful names. This shift in perspective has also impacted the naming of birds, with the American Ornithological Society actively working on a process to rename certain species.

These discussions have prompted a larger conversation about the act of naming itself. Biologists and wildlife enthusiasts now question who has the authority to name species and what responsibility comes with that power. While names serve as labels for identification and classification, they also carry values and reflect the worldviews of those who choose them. Some argue that it is inappropriate to honor any individual, regardless of their virtues or sins, by affixing their name to an entire species.

The push for change gained momentum in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd and incidents of racial injustice. As Confederate statues were being dismantled nationwide, birders called for a reevaluation of problematic eponyms. Organizations such as Bird Names for Birds emerged, advocating for the renaming of all American birds with eponyms. In response to heightened racial awareness, the American Ornithological Society revisited proposals for name changes, leading to the renaming of McCown’s longspur as the thick-billed longspur.

Numerous other eponyms present similar cases that warrant consideration for change, such as the names associated with John Kirk Townsend, John Bachman, and even John James Audubon. The latter, a renowned figure in ornithology, was not without controversy, having committed grave actions such as grave robbing and the selling of slaves. Some chapters of the National Audubon Society have already renamed themselves, but the national society continues to bear Audubon’s name based on strategic considerations.

Critics argue that changing names erases history, but proponents insist that it is a way to clarify the true origins of these names. Many assume that eponyms represent the individuals who discovered the species, but often they are honorifics without a direct connection to birds. Furthermore, the argument that historical figures should not be judged by today’s standards is deemed invalid. Many early naturalists, like Townsend, went against prevailing moral teachings, while marginalized communities have always opposed oppression. The changing of names is not without precedent, as the bird community has previously updated names for better consistency or cultural reasons.

For scientists, the issue of eponyms goes beyond the misdeeds of a few individuals. As European exploration expanded across the globe, it brought with it invasive species and a naming system that replaced native terms. In African and Pacific regions, a significant number of local species are named after Europeans linked to imperial ventures. This highlights the need to confront the legacy of colonialism and the impact it has had on scientific nomenclature.

The conversation surrounding eponyms and the responsibility of naming is ongoing. It raises important questions about representation, historical context, and the role of diversity in decision-making. While there may be resistance to change, the embrace of more inclusive and respectful naming practices signals a step towards a more inclusive and equitable future.

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.