Could a preference for fermented foods have been the catalyst for a remarkable surge in the brain growth rate of our ancestors? According to a perspective study by evolutionary neuroscientist Katherine Bryant of Aix-Marseille University and her US colleagues, the shift from a raw diet to one that included partially fermented food may have played a crucial role in the evolution of our brains.

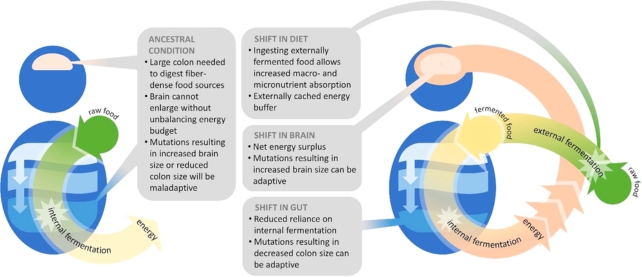

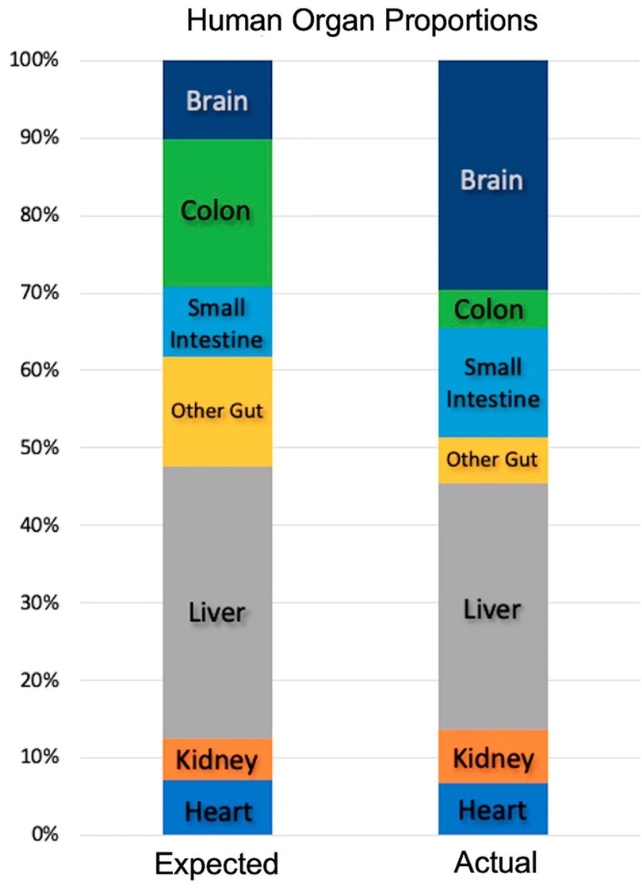

Over the last two million years, human brains have tripled in size while human colons have shrunk by an estimated 74 percent. The mechanisms that allowed energy to be directed to this expansion are complex and debated, but Bryant and her team propose the “external fermentation hypothesis.” This hypothesis suggests that moving intestinal fermentation to an external process may have set the stage for selective brain expansion among our ancestors.

The human gut microbiome acts as a fermenting machine, boosting nutrient absorption during digestion. This process produces energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which powers our metabolism.

The researchers suggest that hominids may have adapted to fermentation much earlier than other proposed explanations for gut-to-brain energy redirection, such as animal hunting and fire-based cooking.

External fermentation, much like cooking, can make food easier to digest and more nutrient rich. Additionally, it may have been a low-entry, stress-free way to access nutritional benefits.

Not only does external fermentation increase nutrient bioavailability, but it can also render poisonous foods edible. “Forethought and mechanistic understanding are not requirements for the initial emergence of external fermentation,” write the researchers.

Looking ahead, the authors conclude that the offloading of gut fermentation into an external cultural practice may have been a pivotal hominin innovation that paved the way for selection for brain expansion.

The study has been published in Communications Biology.