The Importance of Resolving the Issue of Trump’s Disqualification for Presidency

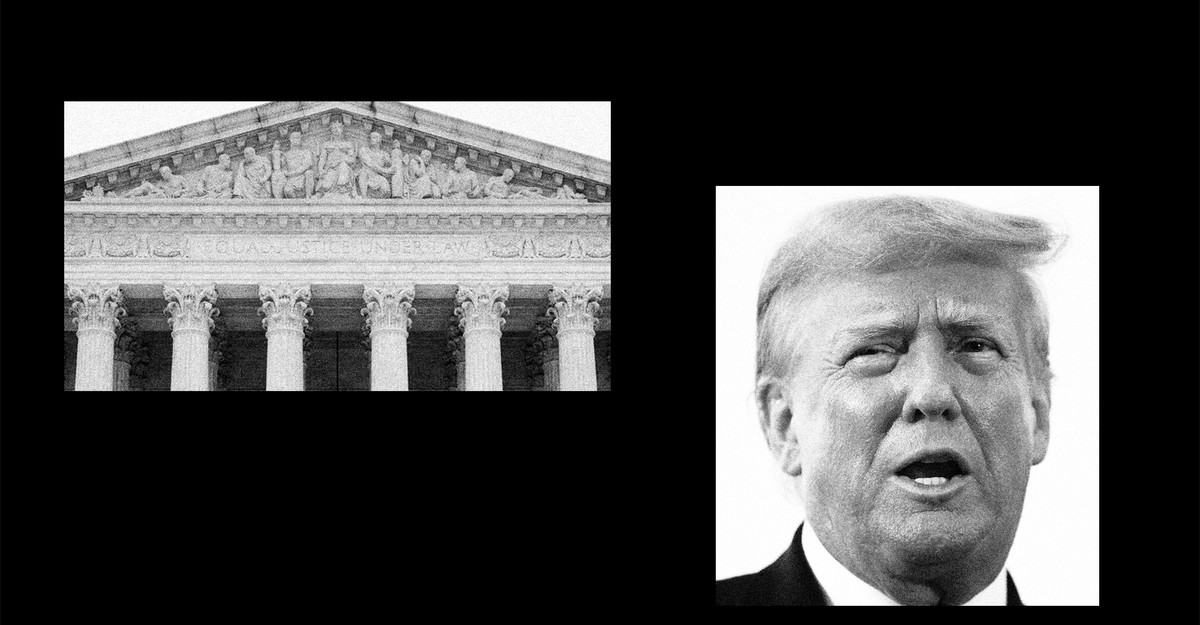

There’s an old saying that sometimes it is more important for the law to be certain than to be right. Certainty allows people to plan their actions knowing what the rules are going to be. Nowhere is this principle more urgent than when it comes to the question of whether Donald Trump’s efforts to subvert the 2020 election results have disqualified him from becoming president again. As cases raising the question have begun working their way through the courts in Colorado, Minnesota, and elsewhere, the country needs the Supreme Court to fully resolve the issue as soon as possible.

Eminent constitutional-law scholars and judges, both conservative and liberal, have made strong cases that Trump is disqualified from being president again under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which bars from office those who have taken an oath to defend the Constitution and then “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.” Some of those scholars are professed originalists—as are many of the Supreme Court’s conservative justices—and to make their cases, they have analyzed what they say is the “original public meaning” of this provision. Other conservative and liberal scholars have concluded otherwise about the clause’s meaning, or at least raised serious doubts about whether and how these provisions apply to Trump.

Among the unresolved issues are whether the disqualification provision applies to those who formerly served as president, rather than in some other office; whether Congress must pass legislation authorizing the Department of Justice to pursue a civil lawsuit in order to bar Trump; whether Trump “engaged” in “insurrection” or “rebellion” or at least gave “aid or comfort” to “the enemies thereof.” Unsurprisingly, given that this provision emerged in response to the Civil War in the 1860s, there is virtually no modern case law fully resolving these issues, and many enormous questions remain on which reasonable minds disagree—for example, who would enforce this provision, and how.

Those are the legal questions. The political questions are, in some ways, even more complicated, and at least as contested. If Trump is disqualified on Fourteenth Amendment grounds, some believe that this would become a regular feature of nasty American politics. Others worry that significant social unrest would result if the leading candidate for one of the country’s major political parties were to be disqualified from running for office rather than giving voters the final say on the issue.

All of these questions, however, are somewhat beside the point. This is not merely an academic exercise. Trump, right now, is already being challenged as constitutionally disqualified, and these issues are going to have to be resolved, sooner or later. My point is that sooner is much better than later.

A number of legal doctrines could lead courts to kick this issue down the road for some time. Maybe the provision applies not to primaries, but only to candidates in a general election. Maybe voters don’t have standing to sue, because they can’t show a particularized injury. Maybe this is a political question to be decided by the political branches, such as Congress, rather than by the judiciary.

But courts should not dally, because judicial delay could result in disaster. Imagine this scenario: Election officials and courts take different positions on whether Trump’s name can appear on the ballot in 2024. The Supreme Court refuses to get involved, citing one of these doctrines for avoiding assessing the case’s merits. Trump appears to win in the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. Democrats control Congress, and when January 6, 2025, arrives and it is time to certify the vote, Democrats say that Trump is ineligible to hold office, and he cannot serve.

As I and my co-authors argue in our report on how to have a fair and legitimate election in 2024, such a scenario raises the possibility of major postelection unrest. The country would have one political party disqualifying the candidate of the other party from serving—after that candidate has apparently won the results of a fair election.

The Supreme Court is the only institution that can definitively say what the law is in this case, and it should not wait once a case reaches its doorstep. Think of Republican voters and candidates soon to participate in the primary process. They, and everyone else, deserve to know whether the leading candidate is actually eligible to serve in office.

A Supreme Court decision to disqualify Trump from the ballot would obviate the need for Congress to resolve the question on January 6. Trump would not be allowed to run. In contrast, a judicial decision that Trump is not disqualified would make it very difficult politically for Democrats in Congress to try to reject Trump anyway after a 2024 victory.

How the Supreme Court would—or should—resolve the question of Trump’s disqualification on the merits is far from clear. There is no question that Trump tried to subvert the results of the 2020 election, using pressure, lies, and even the prospect for violence to overturn Joe Biden’s victory. Trump so far has faced no accountability for his actions: The Senate did not muster the two-thirds vote in 2021 to convict him after his second impeachment, a step that could have led to his disqualification under Congress’s impeachment-related powers. The federal and Georgia cases against Trump for his alleged election interference may yet go to trial, but whether verdicts will ever be reached is far from certain. In any event, even a guilty verdict would not disqualify Trump. If there is going to be any accountability for Trump’s actions in 2020, it might have to come from this disqualification provision. A reading of the Fourteenth Amendment in this way helps protect our democracy.

But serious legal questions continue to dog any use of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. My general view is that to avoid the overall criminalization of politics, reserve prosecuting politicians for instances when both the law and the facts are clear; marginal cases are best left to other remedies. Disqualification, of course, is not a criminal procedure, but borrowing this principle from the criminal context recommends caution here too. In close cases, the voters should get to decide at the ballot box.

The pressure to disqualify Trump is only going to grow until there’s a final resolution of the question. When this issue reaches the Supreme Court, the country will need the Court to decisively resolve it—or risk chaos later on.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.