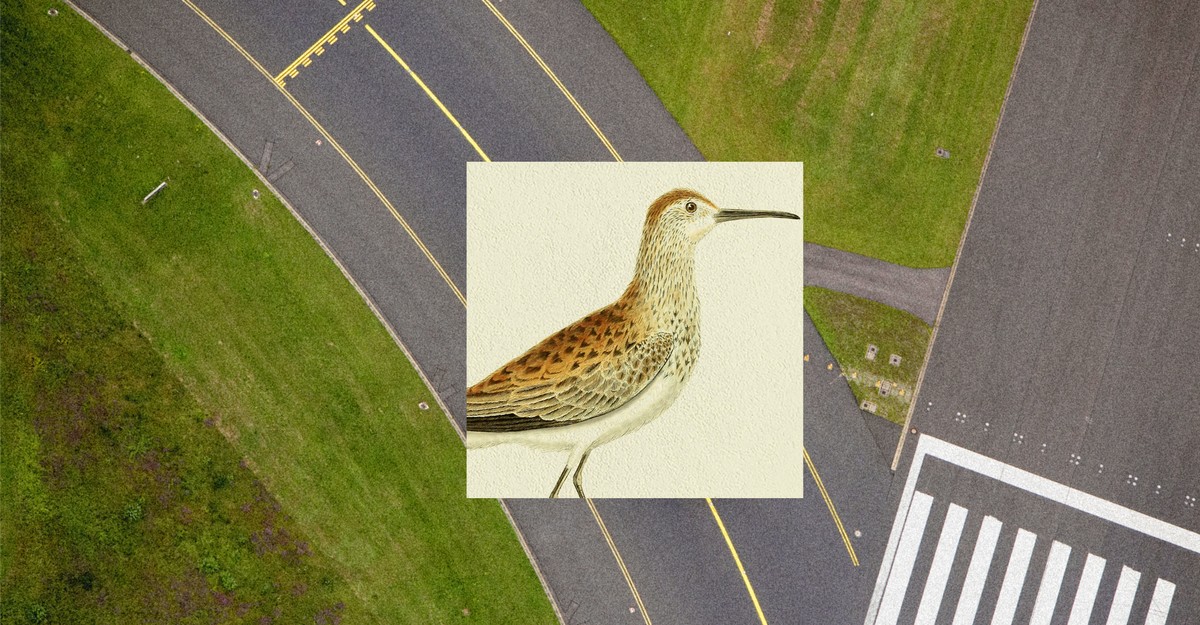

For decades, Portsmouth International Airport in New Hampshire has become an unexpected haven for a frequent flier known as the upland sandpiper. Unlike other passengers, this spindly, brown-freckled bird bypasses security without luggage or identification. Amazingly, the airport’s grasslands have become the only known breeding ground for this native North American species in the entire state. According to wildlife biologist Brett Ferry, approximately seven sandpiper couples nest in the meticulously mowed grasslands each year, producing around a dozen chicks. If the airport were to lose this habitat, it would mean the end of New Hampshire’s breeding population.

This phenomenon is not unique to New Hampshire. Airports around the world are becoming the unexpected refuge for animals displaced by urban development and climate change. Vulnerable butterflies have sought sanctuary near Los Angeles International Airport, an endangered garter snake has found refuge at San Francisco International Airport, and terrapin turtles have caused traffic jams on JFK’s runways while searching for egg-laying sites. However, the grassland birds of the Northeast face the greatest risk and have become increasingly reliant on airports and airfields for survival. The responsibility of preserving these species falls on the shoulders of these travel hubs, which never intended to become conservation sites and often view birds as nuisances.

Grassland birds such as upland sandpipers, eastern meadowlarks, and grasshopper sparrows initially thrived in the Northeast during the 19th century when settlers converted vast land tracts into agricultural fields. However, as farming shifted westward and land was abandoned or developed, the bird populations rapidly declined. Many grasshopper sparrows and eastern meadowlarks are now listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern in northeastern states. Upland sandpipers have even disappeared entirely from Rhode Island and may soon vanish from Vermont. While some birds have found refuge in private farmlands, Maine’s blueberry barrens, and even New York’s landfills, airports have become disproportionately important for their survival.

However, airports were never designed with conservation in mind. The Federal Aviation Administration’s core mission is safe air travel, which often involves making airports less attractive to wildlife. Airport lawns, primarily intended as aesthetically appealing buffers for water runoff and plane skid areas, are regularly mowed and treated with chemicals that can destroy bird nests and disrupt their food sources. Animals that venture onto runways are typically scared off with noise cannons, lasers, and other deterrents. In emergencies, animals that pose a threat may even be shot.

Despite airports’ best efforts to discourage wildlife, some species have flourished in these peculiar habitats. San Francisco International Airport, for example, has become a stable home for the federally-listed endangered San Francisco garter snake and threatened California red-legged frog. However, success stories like these are exceptions. Other airports have seen conflicts arise, resulting in declining bird populations. The decline of burrowing owls at San Jose International Airport in California and the displacement of grassland birds at Meriden-Markham Municipal Airport in Connecticut are just a few examples. The presence of vulnerable species at airports often becomes a burden, especially when they pose a risk to human safety.

Bird strikes pose a significant concern for airports and airlines alike. Since the late 1980s, birds and planes have collided over 220,000 times, with some incidents causing full aircraft downfalls. Even small songbirds can pose a significant threat to planes if they hit them in the wrong spot. Airports implement various strategies to mitigate bird strikes, such as vegetation removal or scare tactics, but these methods do not always prove effective.

In some cases, airports and grassland birds have managed to find a balance. For instance, Pease International Airport in New Hampshire and Westover Air Reserve Base in Massachusetts have become sanctuaries for grassland birds. These sites offer viable habitats that are relatively quiet and less traveled compared to commercial airports. However, these positive examples are few and far between.

The phenomenon of airports becoming unlikely conservation sites highlights the urgent need for wildlife habitat preservation and the potential consequences of human-led environmental changes. The fate of grassland birds and other displaced animals may ultimately depend on the hospitality of bird-averse airports.

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.