Abraham Lincoln: A Political Mastermind

Abraham Lincoln, often romanticized as a noble figure, was, at his core, a skilled politician. He was hailed as a Christlike martyr by his contemporaries, with Tolstoy even dubbing him a “saint of humanity.” However, Lincoln himself humbly claimed to be nothing more than a fortunate instrument serving a greater cause. He understood that engaging in politics was necessary to preserve the nation and effect social change, despite the grimy nature of the work.

Although Lincoln believed slavery to be morally wrong, he recognized the limitations of immediate abolition. The constitutional boundaries and overwhelming opposition from voters prevented him from taking radical actions. Instead, he sought to contain slavery, adapting his perspectives as he gained new insights. It was only when the political climate shifted that Lincoln felt compelled to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

Key to Lincoln’s success was his ability to build alliances with those who disagreed with him. He didn’t shy away from engaging with individuals who considered him outdated, radical, or held conflicting opinions shaped by their unique experiences. My study of 16 face-to-face meetings between Lincoln and his critics revealed that his adeptness in managing these differences played a pivotal role in achieving his goals.

Unfortunately, our impatient and divided society often overlooks this crucial skill of Lincoln’s, sometimes even deeming it weak or naïve. The idea of changing someone’s mind seems almost impossible in our angry and fragmented world. However, these detractors fail to grasp the essence of Lincoln’s achievement. He didn’t aim to drastically alter the beliefs of his critics, nor did they significantly change his. Instead, he focused on making his own beliefs actionable. Starting from a position of minority, he doggedly worked towards creating a majority. Lincoln confronted a seemingly insurmountable social issue and gradually devised strategies to address it, all while steadfastly holding onto his core convictions. Ultimately, he led a coalition of the majority in the Civil War against a minority hell-bent on tearing the nation apart.

As a self-educated lawyer hailing from impoverished roots in Illinois, Lincoln recognized the importance of securing allies in a democracy. He achieved this by appealing to the self-interest of others, supporting their ambitions in exchange for their support. Lincoln embraced the patronage system, providing jobs to his loyalists, and even employed self-interest as a motive when discussing slavery. He warned the predominantly white electorate that ignoring the issue would lead to detrimental consequences. Speaking to their own self-preservation instincts, he urged them to resist slavery, highlighting how its expansion would harm them.

This pragmatic approach made him the ideal leader for the Republican Party, a diverse coalition with members who shared a common belief that slavery was wrong but disagreed on how to end it and integrate freed slaves into society. Could a multiracial republic truly accept millions of emancipated Black individuals as equal citizens? Lincoln often avoided this politically explosive question but occasionally entertained the notion of establishing colonies overseas for Black people.

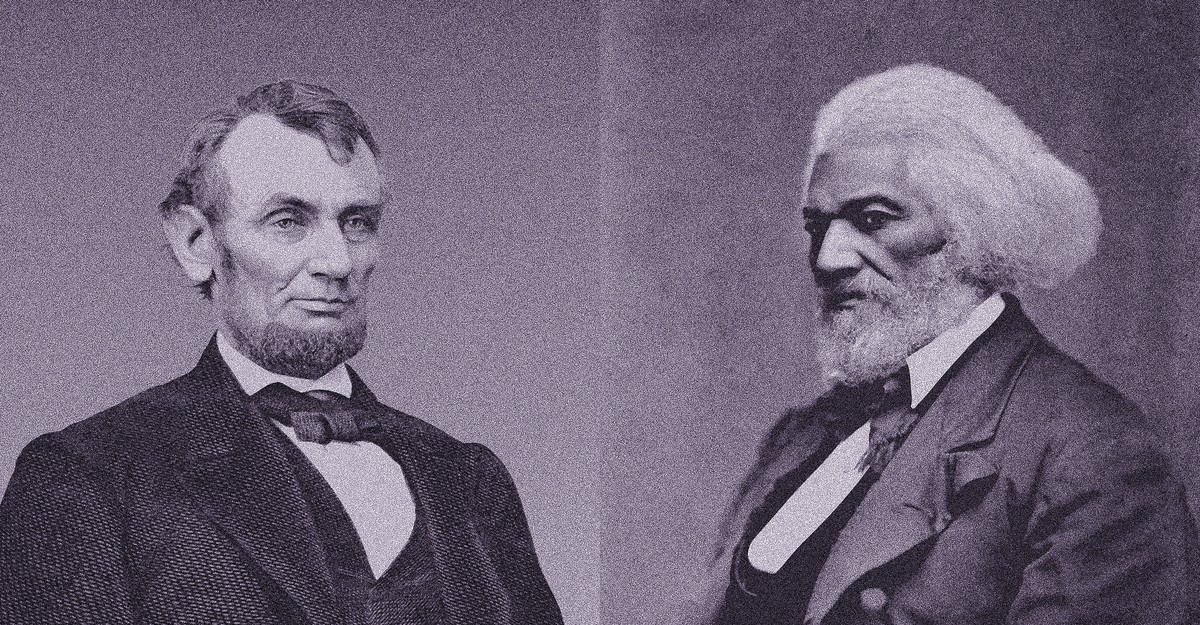

However, on January 1, 1863, Lincoln could no longer sidestep this issue. With the Emancipation Proclamation, he declared freedom for millions of enslaved individuals in areas held by rebel forces during the Civil War. Subsequently, many of these newly liberated individuals joined the Union army, providing what Lincoln referred to as a “double advantage.” The Confederates lost laborers while the Union gained soldiers. However, this service inevitably led to demands for full constitutional rights, as these brave individuals played a crucial role in upholding the Constitution. Sadly, America’s failure to fulfill this promise sparked the central problem of Reconstruction, a long-standing issue still grappling with today. Therefore, it behooves us to examine one of the earliest encounters related to this debate: Lincoln’s meeting with Frederick Douglass on August 10, 1863.

Douglass, a former slave who had escaped from Maryland, had become a prominent abolitionist writer and speaker long before the Civil War. His appearances drew thousands, although he often faced hostility, with mobs hurling rocks to drive him off stage. Conservative newspapers linked his name to Lincoln’s, accusing the Republican Party of following a Black man’s agenda.

In reality, Douglass frequently criticized the president. In his newspaper, he scathingly referred to Lincoln as silly, ridiculous, illogical, hypocritical, and representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred. Douglass accused Lincoln of delaying the Emancipation Proclamation due to laziness until external pressures forced his hand.

Yet, after the proclamation, Douglass agreed to become a recruiter, encouraging Black men to enlist and crush slavery while proving their worthiness as equal citizens. He pledged that these soldiers would receive the same treatment, wages, rations, and protection as their white counterparts. Two of Douglass’s sons even joined the newly formed Black regiment, the 54th Massachusetts, with one becoming a noncommissioned officer.

However, Douglass soon realized that the government had failed to deliver on its promises of equal treatment. Not a single Black officer held a commissioned rank, despite well-connected inexperienced white men assuming positions of authority. Additionally, Black soldiers received a significantly lower monthly pay of $7 compared to $13 given to white soldiers. This injustice infuriated many, and a Black sergeant aptly dubbed it the “Lincoln despotism.”

Black soldiers also believed that they faced greater danger than their white counterparts. While captured white soldiers were generally treated as prisoners of war, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had issued an order stipulating that Black soldiers in captivity would either be returned to slavery or killed. The Black troops implored Lincoln to announce a policy of retaliation, advocating for the execution of a Confederate prisoner for every slain Black soldier. Unfortunately, their pleas fell on deaf ears.

In one aspect alone did Black men attain parity with their white counterparts – the readiness to be thrust into battle. When the 54th Massachusetts deployed around Charleston, South Carolina, the regiment requested the honor of leading an attack on Fort Wagner. They stormed the fort, briefly planting their flag, but were eventually pushed back, suffering heavy casualties. The soldiers of the 54th displayed unwavering devotion to a country that had yet to acknowledge their rights, as noted by The New York Tribune.

The same article touched upon other alleged massacres of Black men, including teamsters in Tennessee, an entire regiment in Louisiana, and every Black prisoner in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Armed with this knowledge, Douglass penned a letter to George Stearns, the head recruiter for the military, recounting these incidents and expressing his disillusionment. He announced that he could no longer in good faith encourage men to fight, stating that the rulers in Washington had failed to live up to their claims of justice, generosity, and enlightenment.

Determined not to lose his invaluable recruiter, Stearns met with Douglass and assured him that the administration was finally addressing his concerns. Lincoln had recently issued an order authorizing retaliation against Confederate prisoners. Encouraged by this development, Stearns suggested that Douglass take his grievances directly to Washington. Before long, Douglass found himself alighting from the train at the District of Columbia depot, a mere two blocks away from the Capitol. The Capitol building boasted a newly constructed white dome, though the Statue of Freedom had yet to be installed.

Anticipating a considerable wait at the White House, Douglass encountered a crowded stairway filled with white applicants. He found himself to be the only…

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.