In October of the previous year, Donald Trump initiated a defamation lawsuit against CNN, alleging that they had made derogatory remarks about him, with the first being the comparison to a cult leader. This analogy could potentially flatter Trump, as cult leaders are often portrayed in popular culture as influential figures with almost god-like control over their followers’ lives. Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani was once described by Jimmy Breslin as a “small man in search of a balcony,” so it could be said that Trump is a large man in search of a compound.

Trump stands before massive crowds adorned with symbols showcasing their loyalty, leading them in chants of his name and rallying cries like “Lock her/him up!” and “Build the wall!” These followers refuse to tolerate any criticism of their idol and unquestionably accept his version of events. Similar behaviors can be seen among Taylor Swift fans, although it’s worth noting that they have not resorted to violence like the mob that attacked the Capitol—primarily because Swift has not incited them to do so, at least not yet.

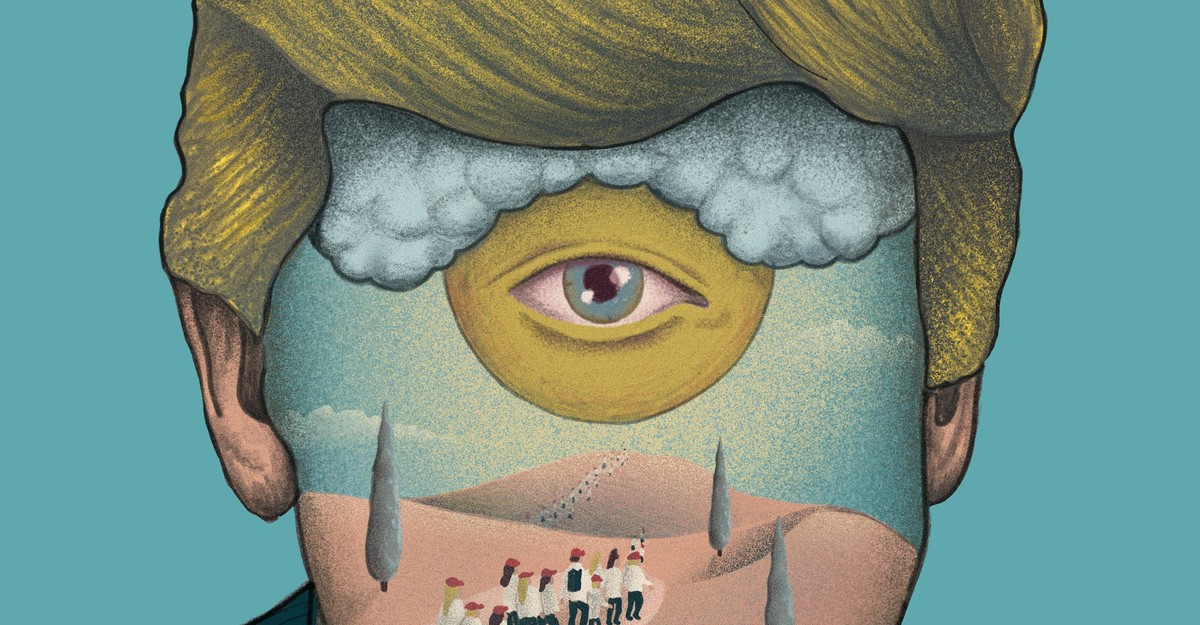

Those who label Trumpism as a cult can support their claim by pointing to the increasing popularity he gained among Republican voters, even in the face of his four criminal indictments. According to a CBS poll in August, these voters trust Trump as their primary source of information more than conservative media, family members, or religious figures.

As the nation confronts a series of trials, both literal and metaphorical, the specific label associated with Trump’s movement becomes less relevant. The pivotal question is not whether Trumpism is a cult, but rather if studying cults can offer any potential solutions to our current situation.

Although Trump’s lawsuit against CNN was dismissed, Diane Benscoter, a cult expert and former cult member, remains steadfast in her comparison of Trump to a cult leader. She has been working with two participants involved in the January 6 events at the behest of their lawyers, not to convince them to recant their beliefs, but rather to assist them in their courtroom behavior and attitude. One of her main goals is to prevent them from making accusatory outbursts about the “deep state.” However, she admits that this work is challenging and slow, even more so than her recent efforts to “deprogram” India Oxenberg, a prominent figure in the NXIVM cult disguised as a self-improvement program.

Benscoter believes that the most promising approach lies in addressing the demand side of cultism. She proposes implementing government initiatives that treat disinformation and indoctrination as a public health emergency, essentially establishing a “Sanitary Commission of the Mind.” Benscoter believes that by educating people on how indoctrination functions, individuals will be better equipped to recognize its influence before falling victim to it. However, one must set aside the ethical and legal concerns associated with granting the government an expansive role in such matters. The potential issue arises from the possibility that it may already be too late to educate individuals about the dangers of joining a political cult by 2023—similar to closing the barn door after the horse has already attacked the West Portico of the Capitol with bear spray.

Steven Hassan, another former cult member, wrote The Cult of Trump in 2019, well before the Capitol attack and before Trump rallied thousands of his supporters indoors without masks during a severe pandemic. Hassan argues that the MAGA movement aligns with his “BITE” model of cult mind control, which covers behavior, information, thought, and emotional control. Like most cult leaders, Trump limits the information his followers receive, demands unwavering loyalty to his ever-changing beliefs, and taps into their primal emotions, not just fear but also joy.

As numerous reports have indicated, Trump’s rallies are euphoric occasions where people revel in cheering and laughter while their perceived enemies are denounced and insulted. According to Hassan, being part of a cult provides individuals with a sense of empowerment, specialness, and being one of the elect, all while standing by someone who supposedly knows all the answers and will lead them to paradise or “make America great again.” This may be the primary reason why Trump’s followers are hesitant to turn away from him—there’s nothing more enjoyable than knowing that you and your friends are the ones who possess all the right answers.

Since the publication of The Cult of Trump, Hassan argues that the movement has only grown stronger, bolstered by alliances with other authoritarian cults like QAnon, as well as organizations such as the Council for National Policy and the New Apostolic Reformation. Digital and social media play a significant role in the movement’s proliferation, acting as platforms that replace traditional sermons and indoctrination sessions. As Hassan notes, individuals spend up to 10 hours a day on their phones, absorbing content from YouTube and other sources. The need for physical compounds to exert control is diminishing due to the ease of online dissemination.

In the 1970s, “deprogrammers” would occasionally be hired by desperate family members to kidnap cult members and isolate them until they renounced their beliefs. However, this approach often backfired, as it only reinforced the cult members’ perception that everyone outside the cult was a dangerous enemy. Additionally, this method was deemed unethical and criminal, resulting in some deprogrammers facing legal consequences for kidnapping.

Today, this strategy is clearly not feasible, as it would require half the country to kidnap the other half, leaving the question of who would care for their pets. On cable TV, liberal pundits attempt to refute Trump’s claims with factual evidence, seemingly trying to lecture his followers into recognizing the truth. However, given the extent of their loyalty to Trump despite numerous scandals, two impeachments, and four indictments, it is unlikely that any new facts could sway them. Admitting they were wrong about one thing would imply that they were wrong about everything, which is a difficult pill to swallow. As anyone who has fallen for a scam and then tried to recoup their losses by playing again knows, admitting that you’ve been deceived is one of the hardest things to do.

Instead of lectures, Hassan suggests adopting a posture of “respectful, curious questioning.” By reconnecting with friends and relatives deeply involved in the MAGA movement and approaching them without judgment, one can remind them of the relationship they shared before their ideological shift. Through gentle inquiry, one can encourage them to consider alternate perspectives and reflect on instances when they have witnessed others being deliberately misled. They can also ask these individuals to imagine what it would be like if they found themselves in a similar situation. Eventually, with this approach, individuals may free themselves from the grip of the cult.

Diane Benscoter attempted a similar method during a conversation with a right-wing conspiracy theorist named Michelle Queen, as documented in an NPR story in 2021. Benscoter initially found common ground by discussing the shared belief that harming children is wrong. However, when discussing the outrageous theories of babies being eaten, Queen expressed her belief in their validity, while Benscoter disagreed. Despite their differences, both parties agreed to continue the conversation—an encouraging sign of open dialogue.

To Daniella Mestyanek Young, every group harbors aspects of cult behavior, and every individual possesses a tendency to become a cult follower to some extent. At 36 years old and armed with a master’s degree in group psychology from Harvard’s Extension School, Young has amassed a following through her series of TikTok videos where she knits while sharing insights from her personal experiences. She was born into the Children of God, which many former members consider a sex cult, and later joined the U.S. Army, only to discover that it too exhibited cult-like characteristics. In her view, all organizations fall somewhere on the “cultiness spectrum,” even revered groups such as the military and Alcoholics Anonymous, which may be much closer to the dark end than commonly believed.

Young incorporates various lists and rules about cults in her TikToks, presenting them in an ever-present text box above her head. One of these lists reads: The…

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.