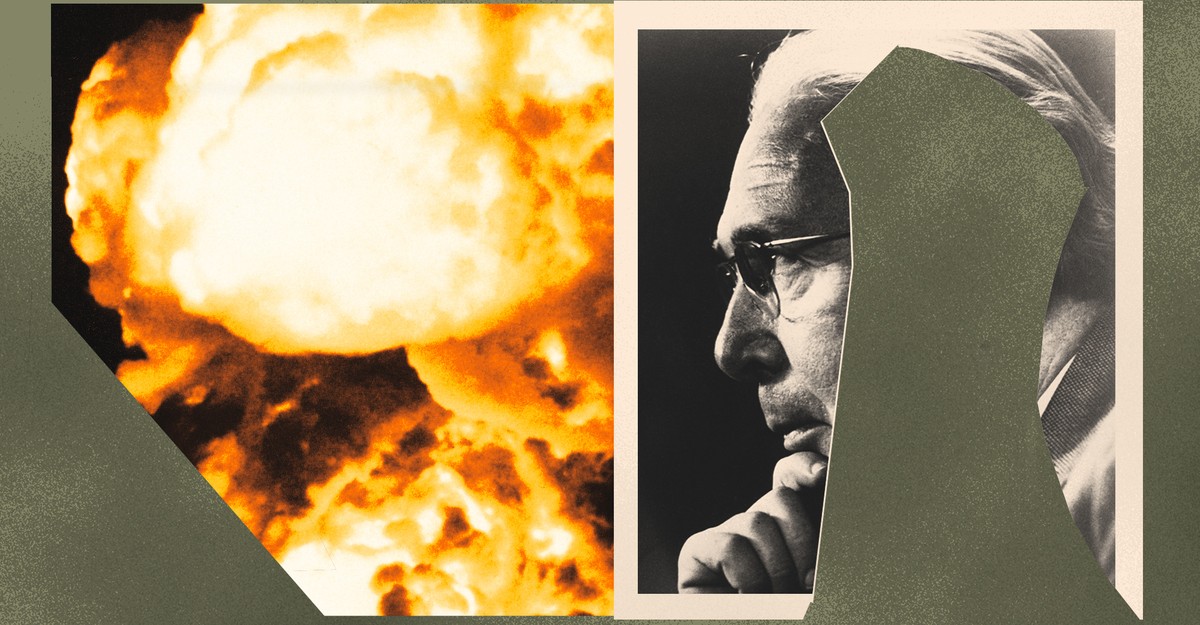

J. Robert Oppenheimer, known as the father of the atomic bomb, grappled for years with the conflict between his scientific pursuits and his moral compass. Through publicly expressing his concerns about the hydrogen bomb and the nuclear arms race, Oppenheimer ultimately became a martyr in the realm of Cold War politics. Fortunately, there were other early nuclear experts, like the scientists at the University of Chicago who initiated a chain reaction, who felt a responsibility to prevent the misuse of atomic science. These scientists recognized a fundamental truth that also applies to today’s pioneers in artificial intelligence and genetic engineering: those who introduce revolutionary advancements must possess both expertise and a moral responsibility to guide society in addressing the potential dangers these advancements pose.

In contemporary laboratories, both within universities and for-profit companies, researchers are now working on technologies that raise profound ethical questions. Can we genetically engineer plants and animals to resist predators without disrupting the natural balance? Should we allow patents on life forms? How do we ethically address perceived abnormalities in human beings? Is it morally acceptable to grant machines the power to make consequential decisions, such as using force in response to a threat or launching a retaliatory nuclear strike? The atomic scientists from Chicago and elsewhere left behind a blueprint for responsible scientific conduct, a blueprint that remains as relevant today as it was during Oppenheimer’s time.

The pursuit of the atom bomb originated in the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago. On December 2, 1942, the first engineered, self-sustaining nuclear-fission reaction took place, marking the beginning of the race. This laboratory brought together a diverse group of scientists, including Leo Szilard, who had played a crucial role in convincing Albert Einstein to warn President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the potential for developing a devastating weapon—knowledge that Hitler’s scientists also possessed. The now-famous Einstein-Szilard letter served as the initial act of scientific responsibility in the nuclear age, propelling the United States toward the Manhattan Project. This illustrates the first lesson learned from the Met Lab: once scientific knowledge is obtained, there is no turning back. Recognizing the transformative power of recent discoveries in nuclear physics, Szilard and his colleagues felt compelled to inform the leaders of their democracy.

Chicago’s atomic village boasted a mix of scientists with diverse backgrounds. Some were young Americans who grew up during the era of New Deal social reforms, while others were Jewish émigrés like Szilard, the German physicist James Franck, and the Russian German biophysicist Eugene Rabinowitch. These émigrés had their own experiences that sensitized them to the ethical dimensions of science. Franck, for instance, had first-hand experience of science’s subjugation to politics when he volunteered for the kaiser’s army and introduced chlorine gas on the battlefield during World War I. Niels Bohr, Franck’s friend and a renowned Danish physicist and Nobel laureate, heavily criticized Franck’s decision, a decision Franck came to deeply regret.

By 1943, the primary focus of nuclear bomb development had shifted to Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico. The scientists remaining at the Met Lab in Chicago had an opportunity to shape the use of nuclear technology during the remainder of World War II and the impending postwar period. The second lesson from the Met Lab is that while scientific discovery may be irreversible, its effects can still be regulated. Historian Alice Kimball Smith chronicles the intense discussions among these scientists during this period in her book, “A Peril and a Hope: The Scientists’ Movement in America, 1945–1947.” The Met Lab scientists ultimately defined lofty yet practical objectives. They aimed to give Japan a glimpse of the atomic bomb’s power, offering them an opportunity to surrender before experiencing its devastation. They also sought to free science from the shackles of official secrecy, prevent an arms race, and design international institutions to govern nuclear technology.

The third lesson from the Met Lab emphasizes that major decisions regarding new technology’s application should be made by civilians in a transparent democratic process. In the mid-1940s, the atomic scientists from Chicago began voicing their concerns to leaders of the Manhattan Project and public officials. While the Army bureaucracy preferred secrecy, the scientists tirelessly opposed this stance. Szilard, Franck, Rabinowitch, Simpson, and many others led the charge to educate politicians and the public about the dangers of nuclear technology. Associations were formed, with the Atomic Scientists of Chicago being among the first. They delivered lectures, wrote opinion pieces, and established publications, most notably the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which was edited and published on the University of Chicago campus. Collaborating with colleagues at other Manhattan Project sites, they rallied support for the passing of the Atomic Energy Act, which created an independent agency comprising civilians accountable to the president and Congress. This agency was tasked with overseeing the development and deployment of nuclear science. Their efforts extended well into the Cold War, with successful campaigns for nuclear test bans, nonproliferation compacts, and arms-control agreements.

In the twenty-first century, decisions regarding the development and deployment of new technologies increasingly occur behind closed doors, in private laboratories and corporate executive suites. This exclusivity impedes collaboration and the open exchange of knowledge, which are vital for scientific progress. Privatizing decision-making processes represents an infringement upon the public’s right to participate, through democratic channels, in ethical decisions related to the application of scientific and technical knowledge. The Met Lab scientists considered these choices to be the public’s responsibility.

In August 1945, two atomic bombs caused the immediate or eventual deaths of 150,000 to 220,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Months later, during a meeting at the White House, Oppenheimer confessed to Harry Truman, “Mr. President, I have blood on my hands.” Truman, however, reminded Oppenheimer that the decision to drop the bombs was his own. Despite their involvement in creating the weapon, the nation’s atomic scientists demonstrated their mettle. The framework they fostered, the template for responsible science, ensured that the use of nuclear weapons in war remained a singular occurrence. We would be wise to heed the lessons they learned.

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.