For the first time, researchers have revealed the reproductive habits of tardigrades, some of the planet’s most resilient creatures.

These minuscule organisms have minimal differences between males and females, making it unlikely that they rely on visual cues to find a mate. Instead, scientists have discovered that females may release a chemical signal that attracts males.

When introduced to a water environment, the males responded to this chemical cue by gravitating towards the females. Interestingly, the females did not exhibit the same attraction, as reported in the November issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Related: Tardigrades’ ability to endure desiccation can be attributed to proteins unique to these creatures

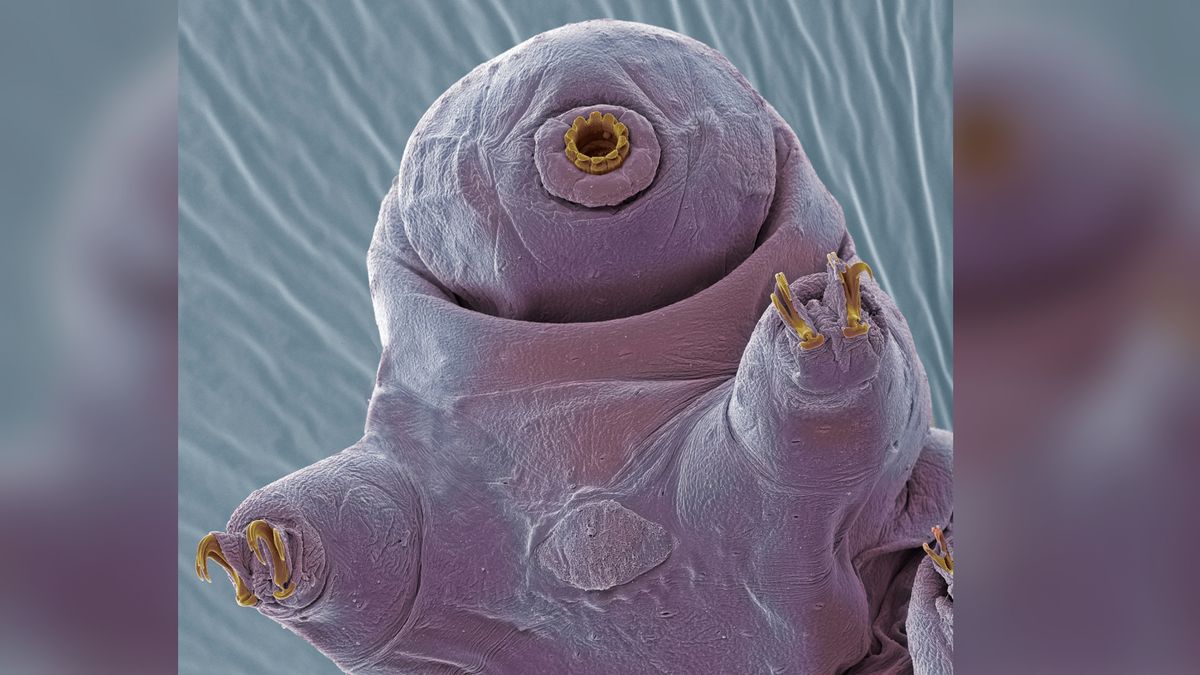

These chubby organisms, also known as “water bears,” boast the remarkable ability to withstand extreme conditions. For instance, they can survive the combined exposure to the vacuum of space, cosmic radiation, and UV radiation. Unlike many other animals, identifying male and female tardigrades proves to be a challenging task due to the absence of clear secondary characteristics despite noticeable size differences.

Due to these challenges, prior to this study, there was limited understanding of how the 1,300 tardigrade species reproduce. A theory speculates that these microorganisms emit chemical cues to signal for potential mates. To test this hypothesis, Justine Chartrain, a doctoral researcher at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland, and her team conducted a series of experiments involving Macrobiotus polonicus species to observe their behaviors upon being exposed to individuals of the opposite sex.

During the experiments, a female and a male water bear were placed in separate containers with another tardigrade in the middle. They then monitored the behavioral patterns of this middle tardigrade. “In the water environment, males were spending more time next to females than next to males,” Chartrain said. This indicated that males were attracted to female tardigrades’ scent, luring them toward the females.

Based on these findings, the researchers pondered whether the tardigrades are capable of following a chemical trail in environments other than water. Consequently, they utilized a Jell-O-like substance known as agar to perform additional tests. These tests revealed that while neither sex followed a path created by other tardigrades, males would sometimes trail behind females after an accidental encounter. In contrast, the females exhibited no active interest in the males, who frequently altered their course to align themselves with the females.

From these results, it is apparent that tardigrades can solely locate opposite-sex mates in water environments and that only the males actively seek out females for the purpose of reproduction.