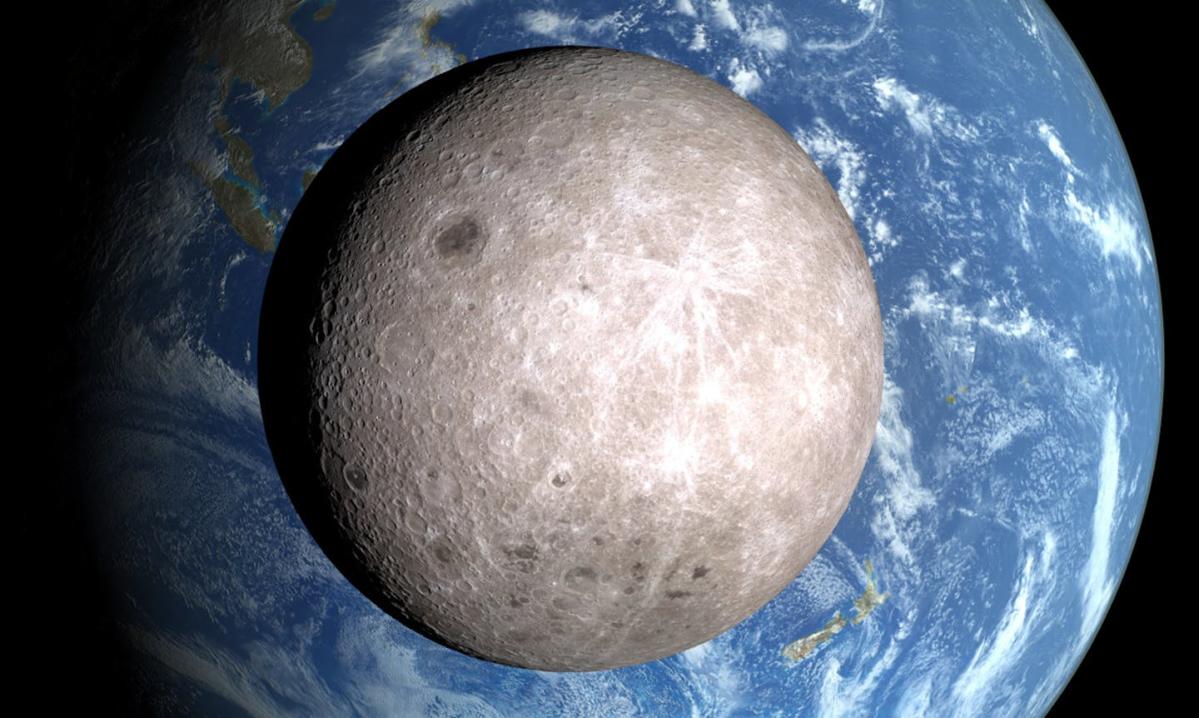

Looking up at the mesmerizing silvery orb of the Moon, you may notice familiar shadows and shapes adorning its face from night to night. This is the same view that our ancient ancestors marveled at as the Moon guided their way in the darkness. Surprisingly, only one side of the Moon is ever visible to us from Earth. It wasn’t until 1959, when the Soviet Spacecraft Luna 3 successfully orbited the Moon and transmitted images back to Earth, that humans were able to catch a glimpse of the “far side” for the first time.

This consistent view of the Moon is a result of a phenomenon known as tidal locking. The Earth and the Moon are in such close proximity that they exert significant gravitational forces on each other. These tidal forces have caused both bodies to gradually slow their rotations and become locked in a synchronized pattern. This phenomenon occurred shortly after the Moon’s formation, which was the result of a collision between a Mars-sized object and the proto-Earth, around 100 million years after the solar system came into existence. As a result, the Moon now completes one orbit around the Earth in the same amount of time it takes to rotate once on its own axis, approximately 28 days. From our vantage point on Earth, we always see the same face of the Moon. Conversely, from the Moon’s surface, the Earth remains fixed in the sky.

The near side of the Moon has been extensively studied because it is visible to us. Astronauts have landed on the near side so that they can maintain communication with NASA here on Earth. All of the samples collected during the Apollo missions are from the near side. However, despite its lack of visibility from Earth, it is incorrect to label the far side of the Moon as the “dark side.” All sides of the Moon experience day and night, similar to the cycles we witness on Earth. Over the course of a single month, each side receives equal amounts of sunlight and darkness. A lunar day lasts approximately two Earth weeks.

Thanks to modern satellite technology, astronomers have fully mapped the lunar surface. Currently, a Chinese mission called Chang’e 4 is exploring the Aitken Basin located on the far side of the Moon. This groundbreaking mission is the first of its kind to successfully land on the far side. Scientists hope that Chang’e 4 will shed light on the surface features of this crater and help answer questions about lunar soil’s ability to support growth. Additionally, despite a recent crash during an attempted landing, a privately funded Israeli mission called Beresheet still managed to receive the Moon Shot Award.

The far side of the Moon provides a unique advantage for researchers due to its natural radio silence. Shielded from human civilization, this area allows scientists to detect weak signals from the universe that would otherwise be drowned out by Earth’s radio and communication signals. Chang’e 4, for example, can observe low-frequency radio light originating from the Sun and beyond, enabling astronomers to gain a deeper understanding of the formation of the universe including the first black holes and stars. Low-frequency radio signals offer a glimpse into the earliest stages of cosmic structures.

Rover missions are also exploring various parts of the Moon’s surface as scientists prepare for future human missions, with the ultimate goal of reaching Mars. One valuable resource found on the Moon is water, which was discovered beneath the Moon’s north and south poles by NASA’s LCROSS satellite in 2009. This discovery has led to the possibility of utilizing the water by breaking it down into hydrogen and oxygen for fuel and breathing purposes.

Researchers are getting closer to exploring the Moon’s polar craters, some of which have perpetually remained in darkness. These deep craters are precisely positioned to never receive sunlight, resulting in permanent darkness on their floors. While there are certainly dark regions on the Moon, it is important to note that the entire far side is not shrouded in darkness.

This article was originally published on The Conversation, a reputable nonprofit news site that shares insights from academic experts. The Conversation is committed to delivering trustworthy news sourced from knowledgeable professionals. Be sure to explore our free newsletters for more informative content.

Author Bio:

Wayne Schlingman is affiliated with The Ohio State University and has no affiliation or financial interest in any organization that may have a direct interest in the subject matter discussed in this article. He also discloses no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.