When Chinese officials and elites criticize Japan, they often mention the atrocities committed by Imperial Japan after invading China in the 1930s. In recent years, Chinese leaders like Xi Jinping have utilized the memory of World War II to justify their nation’s current assertiveness. When Japanese politicians pay their respects at a Tokyo shrine that includes convicted war criminals, it ignites outrage among Chinese patriots.

The reason why these two economic powerhouses in East Asia continue to argue about a war that happened decades ago is because the international attempt to confront the past, particularly the Tokyo war-crimes trial, failed to establish a common understanding of guilt. Unlike the Nuremberg trial for Nazi leaders, which has become a symbol of justice in Germany and its neighboring countries, the Tokyo trial left behind ambiguities and grievances that fuel geopolitical struggles in Asia and also political disputes within China.

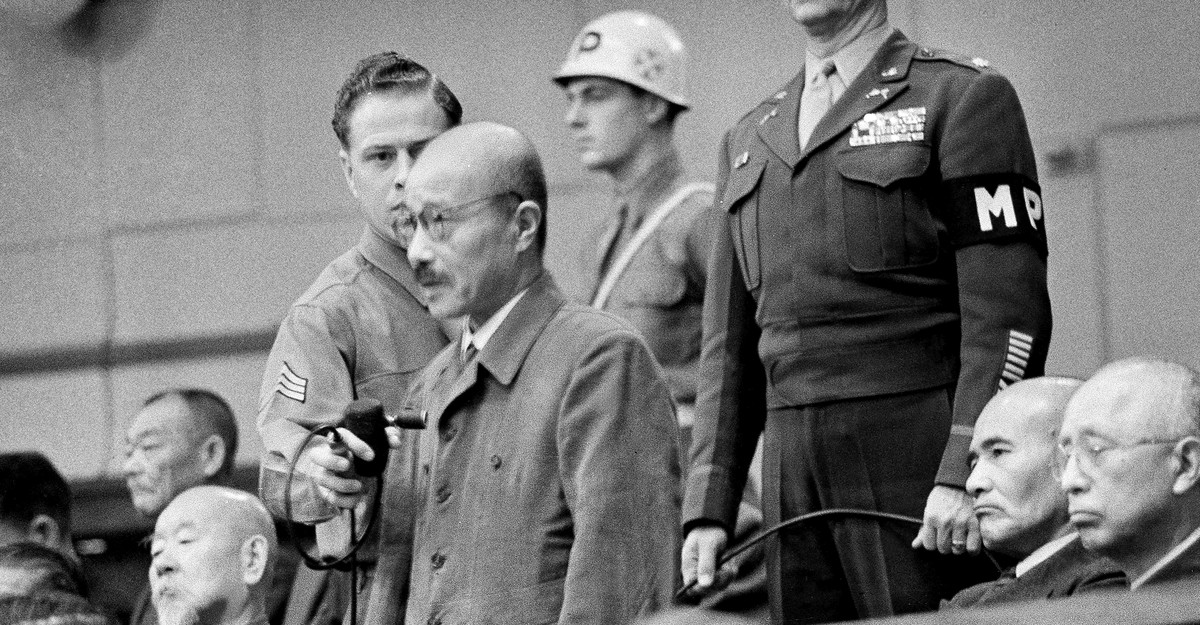

From 1946 to 1948, General Hideki Tojo and 27 other high-ranking Japanese leaders were prosecuted for aggression and war crimes by the victorious Allies. Although the initial proposal was to try Japanese leaders solely for the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Tokyo tribunal became an international affair. Prosecutors and judges from 11 Allied countries, including China, India, and Australia, as well as defense lawyers from Japan and the United States, participated in the trial. Eyewitnesses from China, the United States, the Philippines, and Australia provided chilling testimonies of massacres, rape, and other atrocities committed by the Japanese.

The Chinese judge in the trial, Mei Ruao, was adamant that the suffering of Asians be placed at the forefront of the discussions. Amid debates among the judges about whether aggressive war was a crime under international law, Mei staunchly supported the tribunal’s jurisdiction over Japan’s wartime leaders. In the end, Tojo and six other top officials were sentenced to death by hanging, a decision that brought satisfaction and solace to those who suffered from Japanese aggression, particularly the Chinese.

However, the Tokyo judgment was far from unanimous. The U.S. Supreme Court allowed American defense lawyers to challenge the verdicts, resulting in separate opinions, dissents, and even an acquittal by the Indian judge. While the dissenting opinions portrayed the trial as victors’ justice by colonizing powers, the Indian judge’s stance resonated with Japan and other Asian countries that had bitter memories of imperialism.

The legacy of the trial has influenced China, the only non-Western and anticolonial power among the Allies, in conflicting ways. Xi Jinping has praised the Tokyo convictions and China’s own military tribunals, while Mei Ruao’s experiences after the trial demonstrated that the Chinese Communist Party was not always in favor of such notions.

Mei, born in 1904, had a firsthand experience of the United States and its discriminatory policies towards Chinese immigrants. However, he developed a fondness for the country and its people, appreciating their constitution, education, and democratic values. In 1929, he returned to a tumultuous China and joined Chiang Kai-shek’s National People’s Party. He held various positions within the government, witnessing the invasion by Japan and the subsequent atrocities. He escaped with the government to Chongqing, which suffered heavy bombardment by the Japanese.

The Nationalists were not only fighting Japan but were also engaged in a bitter conflict with the Chinese Communists. The Communists, led by Mao Zedong, demanded revenge but were not interested in war-crimes trials. After Japan’s surrender, an international military tribunal was established, and Mei, chosen for his familiarity with American lawyers, became a judge.

During the trial, Mei pushed for a stern verdict, highlighting that aggressive war was already considered a war crime. He criticized Emperor Hirohito for evading responsibility while his underlings faced trial. After the trial, Mei was offered a high-ranking position by the Nationalist government, but he joined the Communists instead. Praised by Zhou Enlai, Mei became a member of the People’s Congress, adopting Maoist propaganda and abandoning his previous affinity for the United States.

The complex history of the Tokyo war-crimes trial has left lasting impacts on China, Japan, and other Asian countries. The trial’s failure to establish a universal understanding of guilt has contributed to ongoing tensions in the region.

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.