Exploring the Asian American Experience through Memoirs

Updated 4:30 p.m. ET on September 26, 2023.

In today’s age of self-expression, anyone can write a memoir and find an interested audience. The growing number of first-person accounts has led to some truly exceptional works, particularly in the realm of Asian American experiences. These memoirs delve into themes of identity, ranging from racial politics to grief to friendship, providing diverse perspectives on what it means to belong. Furthermore, they tackle bigger questions about marginalization and the historical legacy associated with it.

A recent addition to this genre is Fae Myenne Ng’s “Orphan Bachelors,” a poignant memoir that recounts the author’s family in San Francisco’s Chinatown during the Chinese Exclusion era. This historical memoir stands as a shining example of the impact and significance of first-person storytelling.

The Chinese Exclusion era, lasting from the late 19th century to World War II, saw the United States implementing policies that forbade Chinese immigration and citizenship. The orphan bachelors referred to the men who came to America during this period to work in various industries. Many of them assumed false identities as “paper sons,” claiming to be the offspring of Chinese American citizens. These men faced solitude and the challenges of interracial marriage restrictions, causing immense hardships for those with families in China. Ng refers to them as the “lo wah que” or “old sojourners” in Cantonese.

Ng’s father described Exclusion as a “brilliant crime” due to its bloodless nature, impacting future generations that were never born. Ng and her siblings represented the first wave of repopulation in their neighborhood following the lifting of Exclusion but before the immigration reforms of the 1960s. Beyond sharing her family’s story, Ng sheds light on an enclave frozen in time, altered by the cruel constraints of Exclusion. She emphasizes how Exclusion continues to shape inclusion, showcasing the complex relationship between the two.

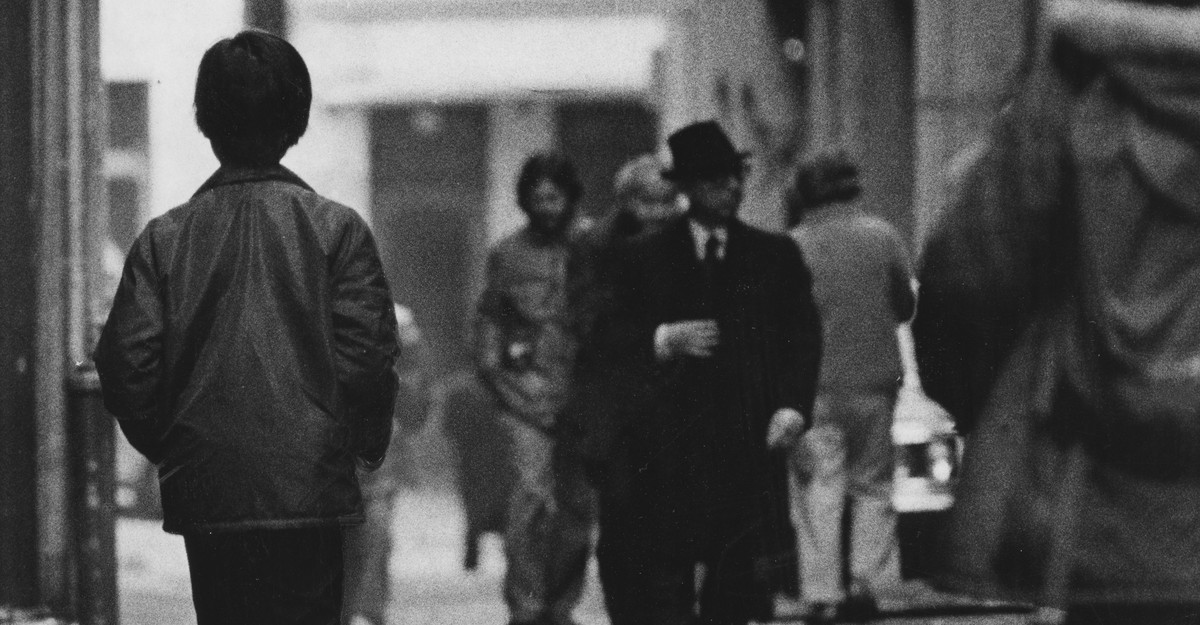

Ng’s father coined the term “orphan bachelors,” conveying the mixture of tragedy, romance, labor, loneliness, and hope experienced by these sojourners. While Ng provides her perspective on their lives, she also brings their colorful stories to life. As young girls, Ng and her sister respectfully referred to these men as “grandfather,” observing them engage in political debates and chess matches at Portsmouth Square. Their distinct personalities were commemorated through names like Gung-fu Bachelor, Newspaper Bachelor, Hakka Bachelor, and Scholar Bachelor. In Ng’s words, they shuffled away, their steps singing a tune of everlasting Chinese American sorrow.

From an early age, Ng demonstrated a passion for history and storytelling, allowing her to perceive the broader currents surrounding her family’s narrative. She spends time with Scholar Bachelor, residing in an SRO hotel, working in a restaurant, and teaching at the Chinese school where immigrant children attended after their regular English classes. Scholar Bachelor, a stern yet encouraging teacher who recited Tang dynasty poetry, inspired Ng to seek inspiration from her ancestral homeland in her writing pursuits.

Another orphan bachelor who profoundly influenced Ng was her father. As a merchant seaman and storyteller, he had a talent for transforming facts into captivating legends. He had spent nearly a decade in San Francisco’s Chinatown before returning to his ancestral village in China to find a wife. Together, they came back to California to start a family after the lifting of Exclusion. Like many who faced unjust barriers and continued precarity, he wove tales of warlord violence, famine, and adversity, serving as a form of currency among the orphan bachelors in the park. These stories provided perspective, reminding them that their current misfortunes were not the worst they had endured. While life in America may have been challenging, it paled in comparison to China.

The inclination to share tales of hardship and claim ownership over them is evident in Ng’s parents’ relationship. Both filled with pity for themselves and others, they had little in common aside from their mutual suffering. Their competitions in recounting their experiences contributed to the ongoing turmoil in their marriage. Ng’s father eventually left on merchant ships for extended periods, seeking respite from the constant fighting. Meanwhile, her mother worked as a seamstress, stitching at a factory during the day and at home at night, the sound of the sewing machine lulling Ng and her sister to sleep and waking them up in the morning.

This is not a story of upward mobility or assimilation. The battles and hardships persist even after Ng’s parents purchase a small grocery store and a house on the outskirts of the city. In the 1960s, Ng’s father participates in the U.S. government’s Chinese Confession Program, allowing paper sons to confess their false identities in exchange for the possibility of legal status. Yet, the program is controversial, as a single confession implicates an entire lineage, with no guarantee of achieving legal status, often leading to deportation. Ng’s mother pressures her father to confess, hoping to bring her long-lost mother to the United States. However, his confession invalidates his legal status, and it takes many years before his citizenship is restored.

The act of confession destroys their marriage. Nevertheless, small displays of devotion persist. During a time of mourning for Ng’s mother, her father journeys to Hong Kong and returns with a jar of snake’s gallbladders, believed to restore courage. He tenderly feeds it to her, sitting by her bedside. This ongoing tension within their relationship is one of the memoir’s remarkable qualities. On the surface, it is a story about the struggles and dramas of a single family, yet its scope transcends the personal, delving into the unjust restraints that make unhappiness feel inevitable. It highlights the significance of steadfast loyalty in keeping a family intact.

One of the things Ng’s father, the master storyteller, imparts on her is the presence of secrets within every tale. He encourages her to uncover the hidden truth within stories. “Orphan Bachelors” can be seen as just that—a deep excavation that builds upon Ng’s previous work. Three decades ago, Ng’s debut novel, “Bone,” presented a version of this story. Similarly focused on a family in San Francisco’s Chinatown during the Confession era, “Bone” delves into the complexities of a mother who is a seamstress, a stepfather who is a merchant seaman, and the eldest daughter as the first-person protagonist. The novel revolves around the suicide of the middle daughter, a tragedy that forces the family to confront the lies that have plagued their relationships and the larger falsehoods that have shaped the lives of paper sons.

“Bone” captivates readers with its minimalist yet vivid descriptions, incorporating details like a chicken being plucked until fully bald and culottes sewn to meet the demands of the flower-power ’60s. In “Orphan Bachelors,” Ng enriches the atmosphere by paying attention to linguistic subtleties. She recognizes the significance of language in shaping identity—its ability to create, empower, deny, and obscure. Her portrayal of the Cantonese subdialect she hears…

Denial of responsibility! Vigour Times is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.