In the June 1940 edition of The Atlantic, the renowned African American author Richard Wright responded to a review of his newly published novel, Native Son, which had appeared in the previous month’s issue of this magazine. Wright’s rebuttal, titled “I Bite the Hand That Feeds Me,” criticized the reviewer for numerous misinterpretations, particularly regarding the characterization of the novel’s protagonist, Bigger Thomas. However, one of the most striking lines in Wright’s response was an observation unrelated to the setting of Native Son in Chicago or the birthplaces of Wright and the critic, David L. Cohn, in Mississippi. After asserting that “the Negro problem in America is not beyond solution,” Wright parenthetically mentioned a core tension in his future work: “I write from a country—Mexico—where people of all races and colors live in harmony and without racial prejudices or theories of racial superiority. Whites and Indians live and work and die here, always resisting the attempts of Anglo-Saxon tourists and industrialists to introduce racial hate and discrimination.”

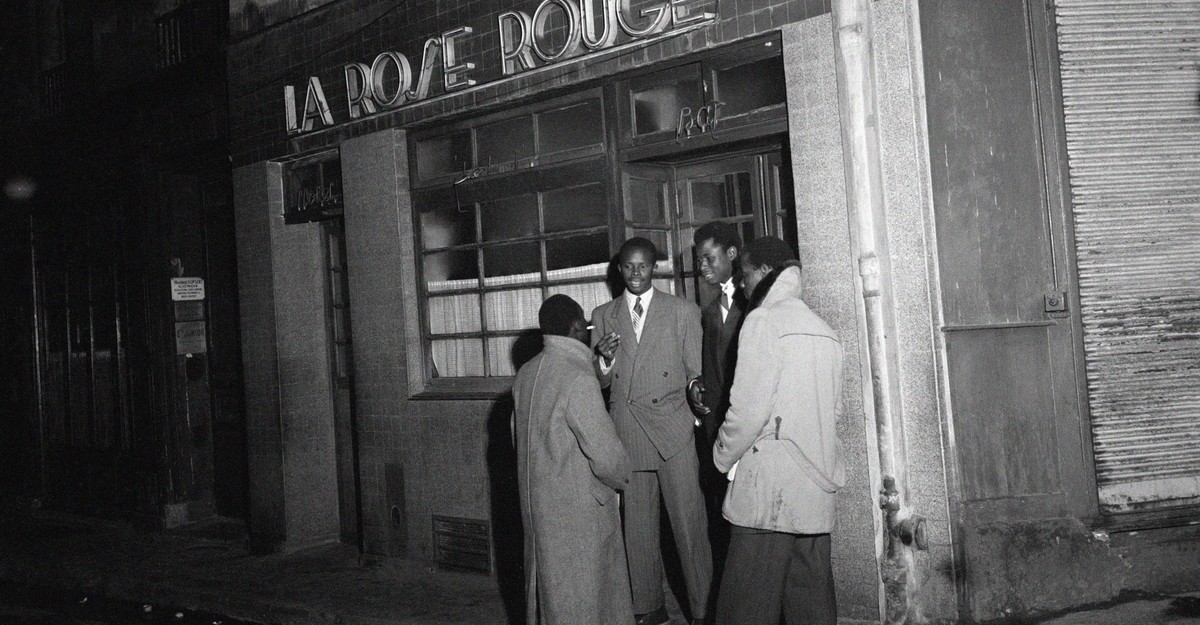

Wright’s perspective on racism as a uniquely American issue would continue to emerge throughout his body of work—most notably in his unpublished but later discovered 1951 essay, “I Choose Exile,” in which Wright poetically praised France as “above all, a land of refuge.” Wright was not the first Black American creative figure to find artistic freedom and relative safety only after leaving the United States. Paris became a haven for Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, William Gardner Smith, and other Black American performers and intellectuals in the 20th century. The allure of finding freedom overseas continues to captivate many even in the 21st century.

Tamara J. Walker’s book, Beyond the Shores: A History of African Americans Abroad, places Wright’s work and politics in context by exploring a different phase of his voluntary exile. Walker traces a lineage of Black Americans who nurtured their creativity through migration, arguing that freedom of movement accompanies freedom of expression. However, she also delves into the complex ways that anti-Black racism manifested both within the United States and in the countries where her subjects sought refuge. For instance, Wright’s time in Buenos Aires in 1950, during the shooting of the first film adaptation of Native Son, was a dark period that he rarely mentioned in his own work. By examining his experience within a broader tradition of Black diaspora, Walker provides a more nuanced portrait of the trenchant literary figure whose foresight, partly derived from exile, challenges the literary canon.

In the case of Wright, he displayed an overwhelmingly positive attitude towards his years in Europe, particularly in Paris. He wrote about his time in Paris with great enthusiasm, maintaining until his death in 1960 that “there is more freedom in one square block of Paris than there is in the entire United States of America!” However, Baldwin and Gardner Smith rejected Wright’s view of Paris as a racial utopia, although they did find some comfort and success there. Shortly after Wright’s death, Baldwin published “Alas, Poor Richard,” a poignant account of their fractured friendship in which he criticized Wright for idealizing a country that “would not have been a city of refuge for us if we had not been armed with American passports.”

Walker, an associate professor of Africana studies at Barnard College of Columbia University, tackles this contradiction in her book. Each chapter of Beyond the Shores tells the story of one or two individuals, many of whom are artists, who traveled to different places during specific decades. The book explores well-known destinations like Paris, London, and post-World War II Germany, as well as lesser-known places with limited research on the presence of Black Americans. Walker’s skillful connections across chapters and narratives reveal changes in policies, social movements, and prevalent attitudes in the United States as well as other countries. For example, the chapter on Richard Wright’s time in Argentina highlights how the fear of backlash from the United States prevented other nations, including France, from hosting film adaptations of Native Son. Censorship followed Wright beyond American borders, with Spanish-language translations of the film titled Sangre Negra instead of Hijo Nativo, which would have fostered greater identification with the protagonist.

The first chapter introduces Florence Mills, a singer and actor born in Washington, D.C., who made her debut in Paris in 1926 at the age of 30. Mills had been performing for two decades across the United States, receiving rave reviews in productions such as the all-Black Broadway musical Shuffle Along. However, Mills understood that her success on Broadway would not translate to Hollywood opportunities like it did for white actors. When the impresario of Blackbirds, the revue she was headlining, secured a Paris run, Mills took a leap of faith and moved to the city where she had heard of more chances for Black singers, vaudeville acts, and cabaret performers.

In Paris, Mills drew immediate comparisons to Josephine Baker, who remains an influential figure in modern cultural production. But Walker goes beyond the superficial resemblance in her account of Mills’s European years. What makes Beyond the Shores so compelling is Walker’s detailed description of the environments these immigrants entered when they relocated. She captures not only what they produced but also what they saw, ate, and must have felt. In the vibrant nightlife of the 1920s Paris, where certain areas were dubbed “French Harlem,” Mills and her colleagues could navigate their daily lives and pursue grander stages without being burdened by the oppressive weight of Jim Crow. The Black press in America took note, as evidenced by a headline from the New York Amsterdam News that read, “Colored Artists Holding Sway and Being Treated Like Human Beings by the French.” However, Walker presents a more nuanced picture, highlighting the French organizations that fought against anti-Blackness even as American performers received acclaim. Mills’s time in Paris was not without discrimination, particularly during economic downturns that led to an increase in white American patrons at bars and cafés. Walker approaches these instances of hardship with empathy, just as she does with uncomfortable interactions between Black Americans and other Black individuals encountered during their travels. In some cases, the American passport functioned as a symbol of whiteness. For example, in Nigeria, African American Peace Corps volunteers were alternately called “white black” and “native foreigners,” while Cameroonians referred to one volunteer as…

(HTML tags inline)

Denial of responsibility! VigourTimes is an automatic aggregator of Global media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, and all materials to their authors. For any complaint, please reach us at – [email protected]. We will take necessary action within 24 hours.